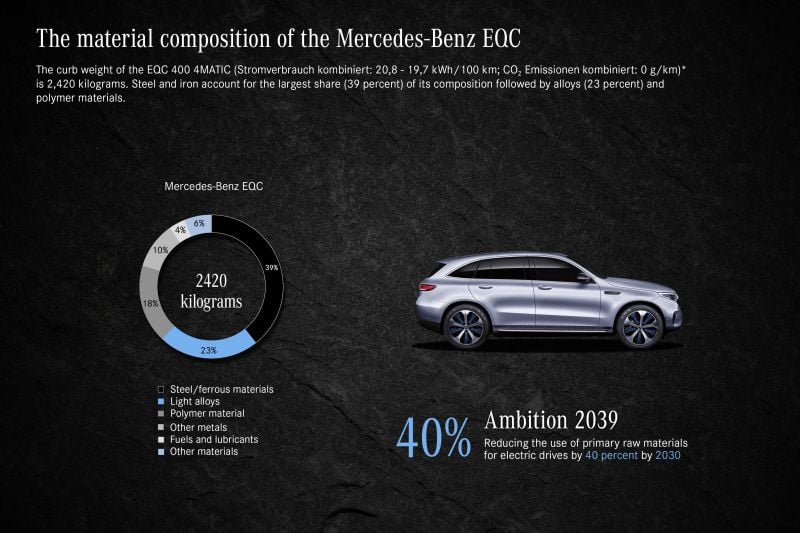

Daimler admits the materials currently used in lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles are unsustainable – but says more transparency, battery recycling and new chemical alternatives are being developed to make electric vehicles cleaner.

The head battery cell researcher at Mercedes-Benz’s parent company, Professor Andreas Hintennach, says there’s still a long road ahead to creating more sustainable, efficient electric vehicle batteries.

“Our activities include the continuous optimisation of the current generation of lithium-ion battery systems, the further development of cells available on the world market and research of next-generation battery systems,” Hinnetach says.

“But of course, there’s more when it comes to batteries for electric vehicles.”

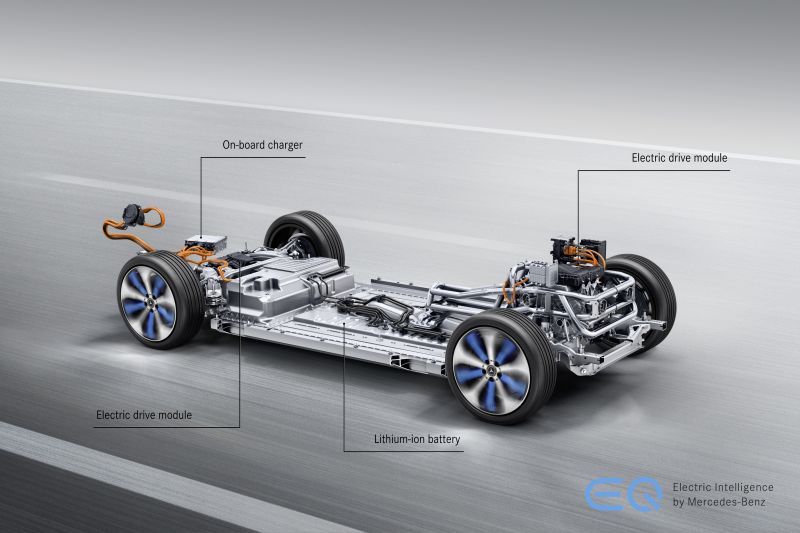

Along with the chemistry of lithium-ion batteries themselves, Daimler is looking into how best to extend battery life with more effective thermal management. But the question of how to most sustainably build batteries in the first place also needs to be addressed.

Cobalt and lithium are both critical to lithium-ion batteries, but mining both carries a huge environment cost.

“Sustainability has become the overarching principle for any development activity at Daimler,” said Hinnetach.

“During development, we create a concept for each vehicle model in which all components and materials are analysed for their suitability in the context of a circular economy.

“Concerning batteries, this concept is already used for fundamental research in which precious materials can be substituted, minimised or used more efficiently. What’s more, recyclability is already taken into account from beginning.”

Cobalt has been associated with violations of human rights and damaging the environment through unethical extraction practices – especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In response, Daimler emphasised the need for transparency in the supply chain, and says it’s already reducing the amount of cobalt in its batteries.

“We have developed an approach that is aimed at making sure that our suppliers meet our requirements with respect to sustainability, and in doing so aim to achieve greater transparency in the supply chain,” Mr Hintennach says.

“From a chemical perspective there are a lot of arguments for abstaining cobalt entirely.

“The more the mixture of materials is reduced, the easier and more efficient it is to recycle. The energy required for chemical production is also reduced because the mixture is easier to produce,” said Hinnetach.

Similarly, lithium is toxic to the environment. Lithium extraction can harm the soil and also causes air contamination. The release of lithium can impact communities, ecosystems and food production.

Cobalt, lithium and other similar materials are mainly based on manganese, a raw material which is less ecologically troublesome and easier to work with.

Daimler says lithium could be replaced with the development of new manganese battery technologies, but they’re unlikely to be commercially viable until closer to 2030.

Lithium-ion batteries will remain in electric vehicles for the foreseeable future, given they are currently the most reliable, efficient option.

Despite the environmental cost involved in development, Daimler argues an electric vehicle is still more environmentally friendly than the equivalent internal-combustion model over its lifetime.

“The battery and the fuel-cell… currently start life with more emissions due to the increased energy requirement. However, in terms of operation they are both much more efficient. And that pays off in the long run,” Hintennach said.

“Even if we do not charge them using CO2-neutral electricity, battery-powered vehicles generate around 40 per cent fewer emissions over their life cycle than vehicles with gasoline engines, and 30 percent less than diesel-powered vehicles.”

There’s also the question of recycling the materials within batteries once they reach the end of their usable life in cars. Daimler forecasts the car industry will focus on recycling and re-using more materials from battery packs.

“In eight to ten years there will be a significant number of vehicle batteries available for recycling. Then in particular cobalt, nickel, copper, and later also silicon will be recycled,” Mr Hintennach predicts.

“We are already very well prepared and the processes are in place, as are the opportunities for returning secondary raw materials into the production cycle. We currently do this with our test batteries.

“The establishment of a functioning market for secondary raw materials for Europe is of great political importance, because Europe barely has any primary sources.”

Some brands are already working on their own in-house battery recycling programs. BMW uses end-of-life i3 batteries in its home energy storage systems.

Although their capacity is lower than when the car was new, the company says ageing batteries are well suited to slower charge/discharge rates common with home storage.

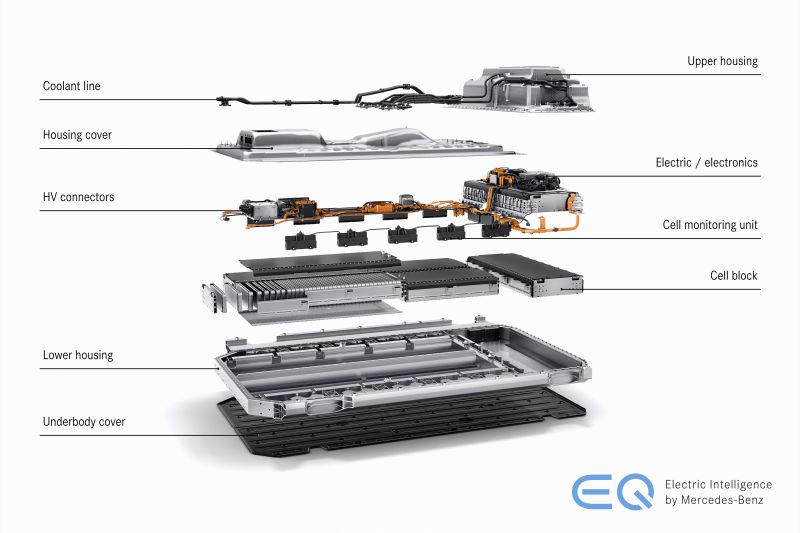

Lithium-ion batteries contain two metal sheets and two poles between them – cathode (positive) and anode (negative) where an electric reaction takes place.

The former is made from a mixture of nickel, manganese and cobalt. Meanwhile, the anode consists of graphite powder, lithium, electrolytes and a separator.

Daimler says silicon, a more recyclable material, will mostly replace graphite powder in the future. It will enable an energy density increase up to 20 to 25 per cent.