Jack Quick

8.4

6 Days Ago

Nissan had a rocky transition from local manufacturer to full-line importer, and the 1980s and 1990s were an interesting era for the brand.

News Editor

News Editor

During the 1970s, Nissan seemed on top of the world.

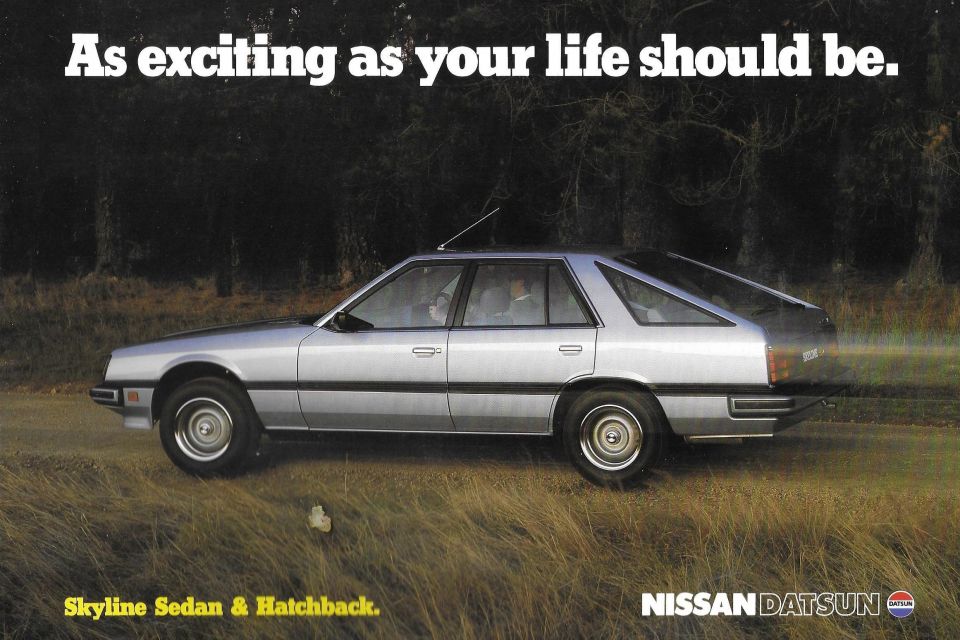

Exporting vehicles under the Datsun name, it was selling up a storm in markets like the UK, US and Australia. Vehicles we malign today like the 120Y were appealing to buyers who simply wanted something more reliable and well-built than they were used to, while cars like the 240Z and 240K/Skyline showed the company could build desirable vehicles, too.

But the 1980s took Nissan down an ominous path. It foolishly dropped the Datsun name and all that established brand equity in favour of the corporate name. In Australia, it began haemorrhaging sales and money in its final years before ending local production.

In the first instalment, we looked at a series of oft-forgotten Nissans from the 1970s and 1980s, so let’s pick up where we left off in the late 1980s.

MORE: 10 Nissan and Datsun vehicles you may have forgotten: Part I MORE: 10 Chryslers you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Fords you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Holdens you may have forgotten about

The Mitsubishi Magna Ralliart. The Leyland P76 Force 7. The TRD Aurion. There have been plenty of Australian-built, Australian-engineered or tuned sporty large cars designed to tackle the Ford and Holden establishment.

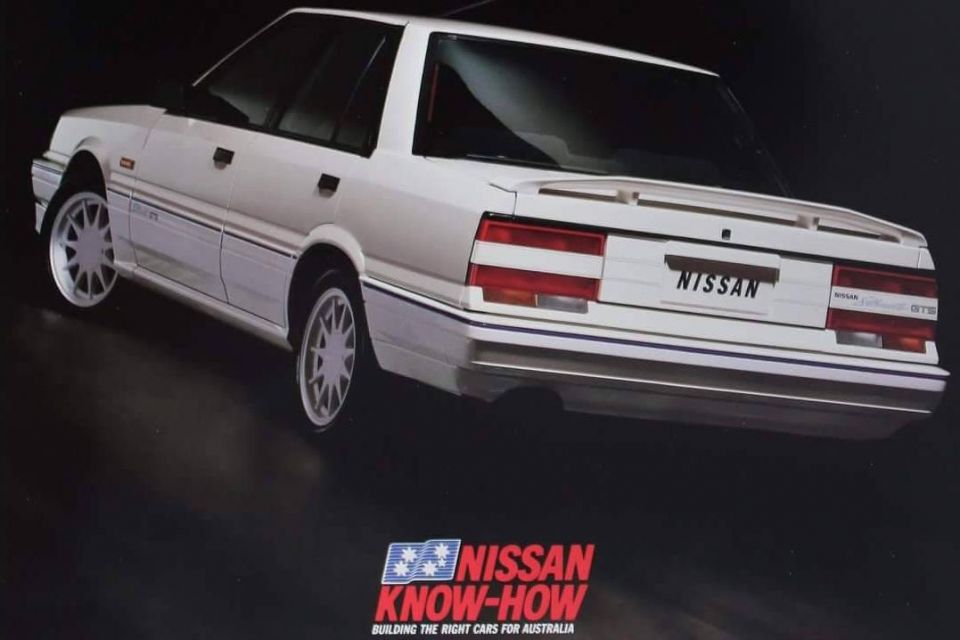

Nissan’s short-lived Special Vehicles Division was responsible for the Skyline Silhouette GTS, a sportier version of its conservative-looking Holden Commodore rival.

The Skyline and Commodore had a connection, too – the VL Commodore that was departing just as the Silhouette GTS was arriving shared its 3.0-litre single-cam inline six-cylinder engine with the Nissan, producing 114kW of power at 5200 rpm and 247Nm of torque at 3600rpm.

The Australian-market R31 Skyline, the first locally-built Skyline, was a somewhat simplified version of the equivalent Japanese-market model in true Nissan Australia fashion.

The independent rear suspension, for example, was swapped out for a live-axle. Turbocharged engines were left at home, despite the presence of a Nissan turbo six in the VL, and Australia also missed out on the more attractive coupe body plus high-tech gadgets like adaptive dampers and digital instruments.

But unlike the Mitsubishi Magna, a widened Aussie version of the Japanese Galant, this big Aussie six was decidedly narrow in Japanese-market fashion. It measured about as wide as a Toyota Corona and 32mm narrower than a VL Commodore.

In addition to four-cylinder models marketed under the separate Pintara line, the R31 Skyline was sold here in GX, Executive, GXE, sporty Silhouette and luxury Ti variants. The Silhouette came standard with a limited-slip differential, unique 15-inch alloy wheels and front sports seats, although it offered no more power than the other models.

Though Nissan teased a turbocharged Skyline with the Super Silhouette Turbo concept from the 1987 Sydney motor show, the first SVD-fettled Skyline remained naturally-aspirated. There was more power, however, with outputs of 130kW at 5500rpm and 255Nm at 3500rpm thanks to a new exhaust system, camshaft and extractors.

Just 200 were produced, all finished in white.

In addition to extra power, the 1988 Silhouette GTS featured retuned suspension with Bilstein struts and thicker anti-roll bars front and rear, plus uprated coils up front, and heavier springs down back.

The front brakes also featured larger 247mm ventilated discs, while the package was finished off with grippier front seats, a Momo steering wheel, unique 16-inch alloy wheels and grille, and a body kit. Some of these parts were borrowed from Nismo in Japan.

Those after the look and less concerned with performance could also briefly buy the Pintara TRX, dusting off the name of an ostensibly sporty Bluebird variant, which featured a body kit but no extra power.

The Skyline Silhouette GTS was actually the second vehicle from the nascent SVD, following a 200-vehicle run of the Pulsar Vector SSS Viscous LSD which included, naturally, viscous coupling plus modest bumps in power and torque.

For 1989, the Silhouette GTS would return, this time based on the GXE and offering a choice of five-speed manual or four-speed automatic transmissions. Mid-1988 had seen the Skyline receive a facelift with a slightly smoother front end plus – finally – the local introduction of the Skyline’s trademark “hotplate” tail lights.

The second-year GTS – or GTS2, as some fans call it – therefore looked racier, helped too by its mandatory Beacon Red paint job. Once again, only 200 were produced.

This was a red car that was actually faster, too. Power and torque were increased to 140kW at 5600 rpm and 270Nm at 4400rpm, and other mechanical changes included an external oil cooler, a shorter final drive ratio and retuned suspension. Aesthetically, there were restyled rear seats to match the front sports seats, plus a new body kit and wheels.

Both iterations of the Silhouette GTS were well-received by critics, and were praised for their smooth engine and road holding ability. They were slower than a Commodore SS, but handled tidier; the GTS2’s improvements over the first GTS were said to make it even more engaging.

In 1988, Nissan sold 10,778 Skylines and 11,615 Pintaras against over 50,000 sales for the Falcon and Commodore, respectively, and an impressive 40,518 examples of the four-cylinder-only Mitsubishi Magna. Nissan’s annual production projections for each were reportedly 14,000 units.

Sadly, the R31 would be the last large, locally-built Nissan.

Even if Nissan had been able to bring the new R32 Skyline to Australia, or even an Australianised Maxima or Laurel, there likely would have been no interest from other automakers in rebadging the model as was being expected from local manufacturers under the Button Plan.

Not to mention, both the R32 Skyline’s smaller dimensions and its availability only as a two-door coupe or four-door hardtop sedan put the kibosh on it coming here in anything other than a hot GT-R.

The front-wheel drive Maxima did come here in 1990, but as an import and with a base price higher than even the most expensive Skyline. There’d be no wagon, and there’d be no locally-tuned performance models.

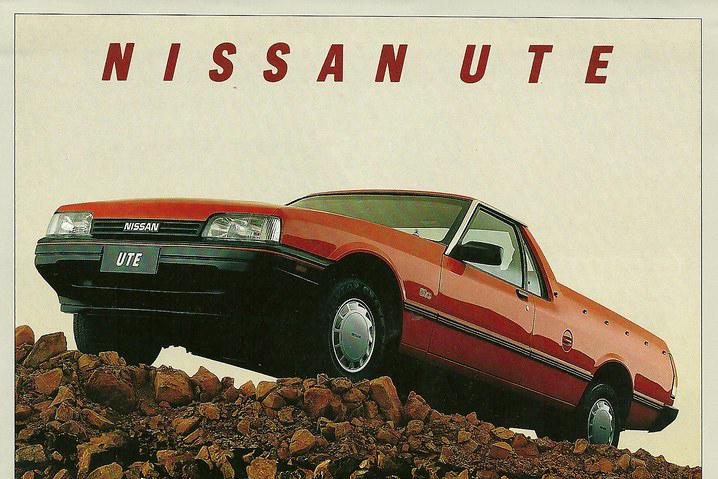

The Button Plan, as it was popularly known, led to some long-running rebadged vehicles, even if most of them didn’t light up the sales charts. It also produced some short-lived, bizarre rebadges, too.

It was an Australian Government initiative to rationalise the local car industry, and was named for Senator John Button, then Minister for Commerce, Trade and Industry.

By the time the Plan was announced, thirteen models were being assembled by various manufacturers and import quotas and tariffs had been instated to protect them. The Button Plan aimed to cut that number of protected vehicles to six models and thus force the industry to consolidate, in theory strengthening the local products’ competitiveness before tariffs were to be gradually reduced. Of the local automakers, only Mitsubishi didn’t participate.

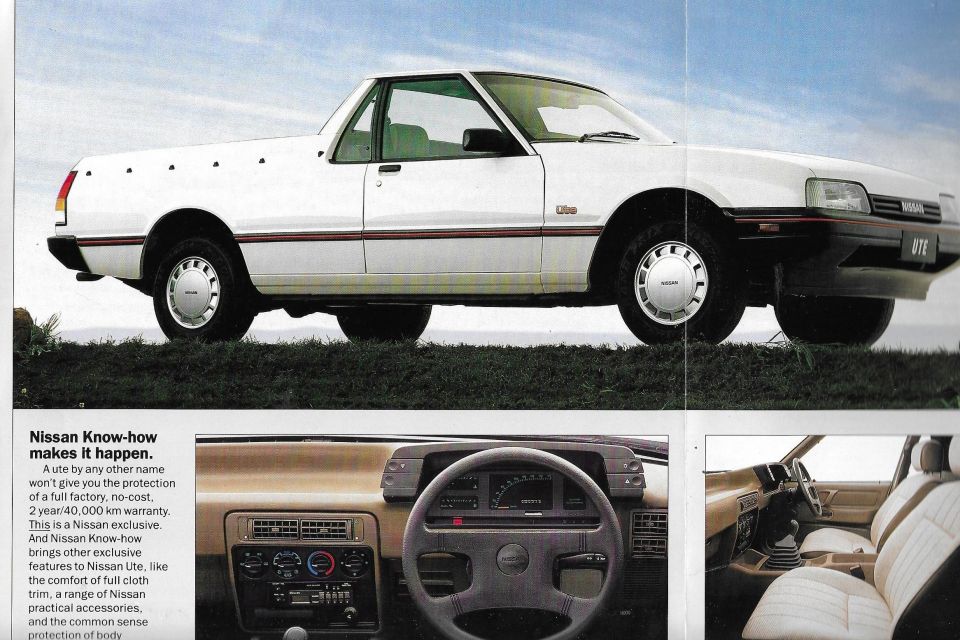

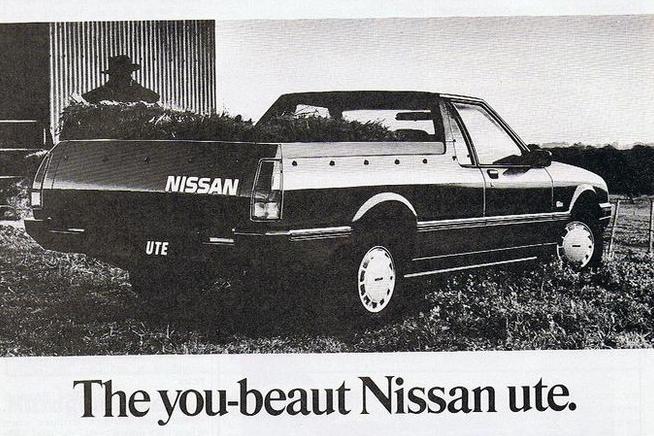

A rebadged Ford XF Falcon ute, the Nissan Ute – sometimes referred to as The Ute – differed only in the badges and centre cap of the steering wheel, with some Nissan stickers pasted on for good measure.

Sold from 1989 to 1992, Nissan offered it in a choice of DX and ST trims, both with a carbureted 4.1-litre six-cylinder engine producing 103kW of power and 316Nm of torque. A column-mounted three-speed manual was standard, with a five-speed floor-shift standard in the ST. A three-speed automatic was also available.

DX models had a front bench, while the ST had front buckets and added power steering, a driver’s footrest, and a tilting steering column. Pricing was essentially identical to the equivalent Ford-badged product.

Overlooked then and forgotten today, the Nissan did have one ace up its sleeve: a two-year, 40,000km warranty, twice as long as the Ford’s (ah, the bad old days). A clever buyer would therefore get a good deal at Nissan, enjoy the longer warranty, and just peel off the stickers.

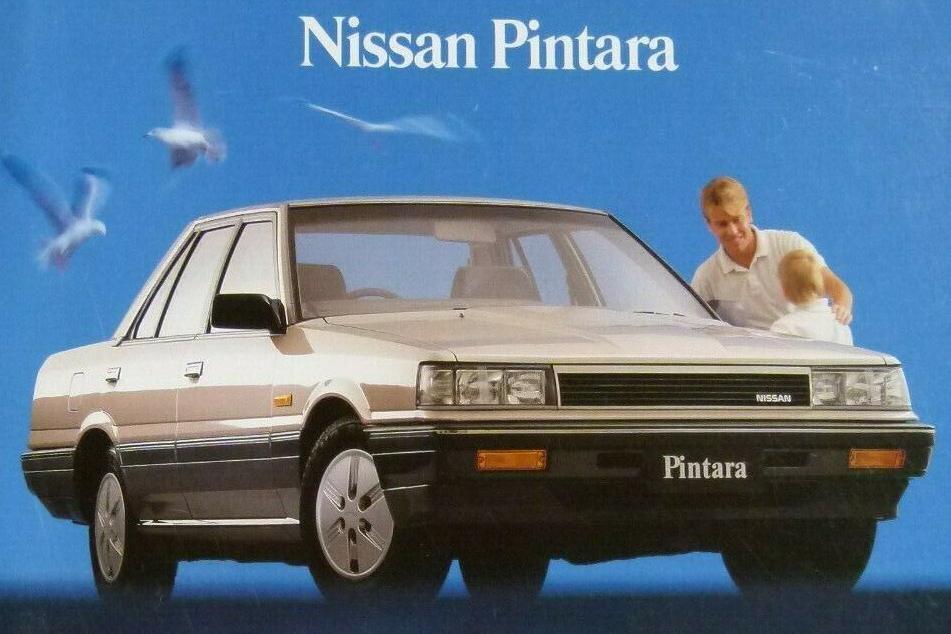

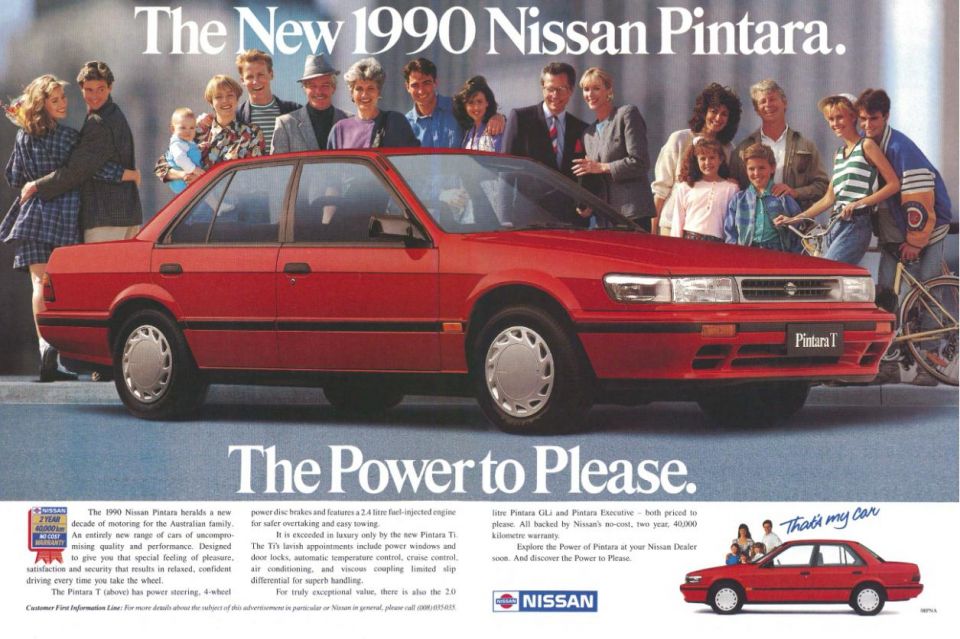

As the Skyline was being sunsetted, a new Pintara was being introduced.

The front-wheel drive U12 Bluebird was foisted upon Nissan Australia as the Pintara – initially referred to as Project Matilda – even though the local arm had wanted to retain a rear-wheel drive large car or, at the very least, an Australianised Maxima.

The Australian Government’s Button Plan also saw the new (but not that new) Pintara get twinned with a rebadged Ford called the Corsair, though Ford sold it alongside an imported, Mazda 626-based Telstar TX5 hatchback.

Nissan had been building front-wheel drive Bluebirds since 1983 but the local arm had stubbornly resisted the shift from rear-wheel drive; it had company, as its rear-wheel drive Toyota Corona and Mitsubishi Sigma rivals persisted in Australia even as they were being phased out elsewhere.

But with the front-wheel drive Magna – a widened, Australianised Galant – selling up a storm and Toyota introducing its first locally-built Camry in 1987, Nissan belatedly followed the herd.

There was nothing exciting here, with the turbocharged and four-wheel drive options remaining in Japan along with the sleeker four-door “hardtop” body style. Instead, the locally-built Pintara was offered with a choice of two naturally-aspirated, fuel-injected four-cylinder engines.

GLi and Executive models used a 2.0-litre with 83kW and 168Nm, while the T, sporty TR.X and lux Ti used a 2.4-litre with 96kW and 189Nm. Five-speed manual and four-speed automatic transmissions were offered with each.

There was no six like the Skyline had (the imported Maxima aimed to fill that gap in the range), nor was there a widened body for Australia like the Mitsubishi Magna despite it being well-known Toyota was working on a wide-body Camry.

All models featured four-wheel independent suspension, with TR.X and Ti models featuring a viscous-coupling limited-slip differential and the TR.X including a firmer suspension tune. The Pintara’s price range was about lineball with the rival Camry, and the 2.4-litre engine was a bright spot in an otherwise uneven package.

Contemporary reviews criticised the so-so dynamics and poor finish of the new Nissan, with the company not building the Pintara to the same high standard as the rival Camry.

While the Holden Apollo, Mitsubishi Magna and Toyota Camry offered a choice of sedan or wagon bodies, Nissan tried to split the difference between a wagon and a hatch with the locally-designed Superhatch. This was reportedly due to Nissan wanting a wagon but Ford wanting a hatch. Available in all bar TR.X trim, it arrived a year after the sedan but it failed to boost sagging sales.

Nissan planned to export around 10,000 units of the Superhatch to Japan, where it was known as the Bluebird Aussie. While production numbers aren’t readily available, we suspect it fell short of said goal. This wasn’t the only time a Japanese automaker would import cars to its home market from its outposts – Mitsubishi would later do this with the Aussie-built Magna/Verada wagon (Diamante), and Honda also imported US-built Accords.

In 1990, Nissan sold 13,688 Pintaras, likely including some lameduck R31 wagons. That put it narrowly ahead of the by now imported Ford Telstar and Mazda 626’s combined sales but well adrift of the circa-31,000 tallies of the Camry and Magna. Ford sold just 7631 Corsairs.

Sales fell to 11,819 in 1991, and then the plug was pulled in 1992. Reported production targets of 40-50,000 vehicles per year in hindsight appear quite optimistic, even taking into account exports to Japan and New Zealand.

Nissan Australia, like Holden, had been bleeding red ink during the 1980s with successive annual losses. The Pintara, as well as the N14 Pulsar of 1991, had been intended to correct the brand’s course in Australia, and Nissan HQ had invested heavily in the Clayton plant to build these with aims to export vehicles as far afield as Europe.

With the Pulsar, Nissan had tried to correct its years of over-discounting by offering a fresh, more desirable but more expensive package, and sales had fallen.

The Pintara, in contrast, entered a segment with a package that was neither exceptionally fresh nor particularly well-built or engaging to drive, and it had floundered and then foundered. Even Ivan Deveson, head of Nissan Australia from 1987 to 1991, later reportedly admitted the car was a mistake but one that had been signed off before he joined the company.

Nissan Australia lost $125 million in 1991 and local production at the company’s Clayton plant was terminated the following year, with 1800 jobs lost. Embarrassingly for Nissan, it was the first time it had had to shutter a plant overseas. Even if the Pintara alone wasn’t the cause of death for Nissan’s local manufacturing, it sure didn’t do a thing to save it.

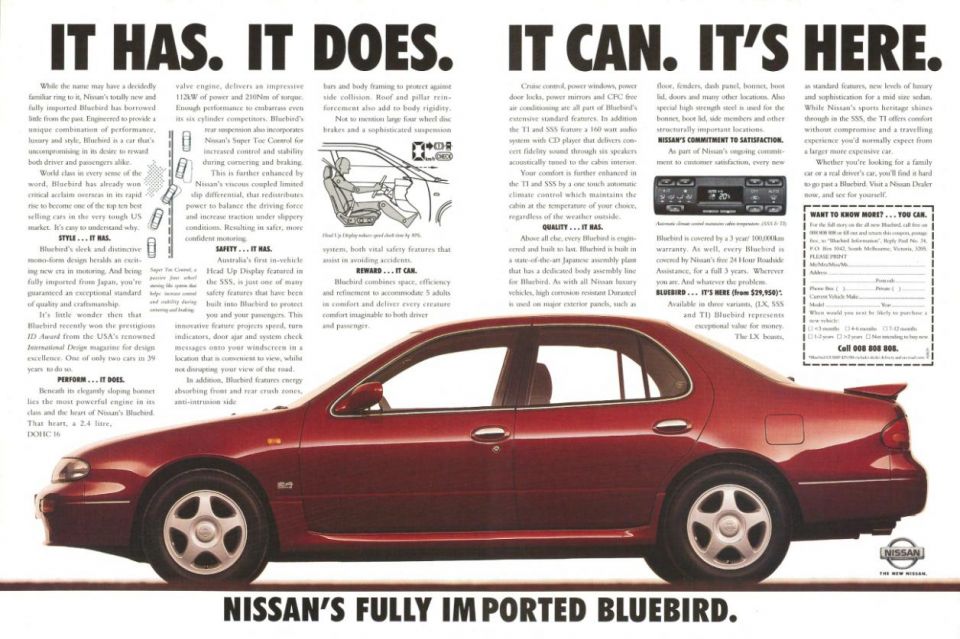

The Bluebird might just be one of the best mid-sizers Nissan has ever sold in Australia, and yet it proved to be short-lived.

None of its predecessors – the 180B, 200B, Bluebird and Pintara – could be called inspiring. The Bluebird, in particular, was a rather stodgy sedan and wagon clinging onto rear-wheel drive as more modern rivals – and, indeed, mid-sized Nissans overseas – switched to front-wheel drive.

Its rear-wheel drive Pintara successor was similarly conservative and Nissan appeared to have forgotten to style it, while the front-wheel drive Pintara promised much and disappointed.

As the defunct Pintara was an Australianised version of the Bluebird 910, known in the US as the Stanza, its replacement would be the next generation of Bluebird, series name U13. It arrived here in 1993, roughly a year after the Pintara was discontinued.

Sold in the US as the Stanza Altima and later just Altima, this Bluebird came from Nissan’s California design studio. Its rounded lines were thoroughly contemporary in the 1990s, an era of organic styling, and bore a resemblance to those of the rear-wheel drive Infiniti J30.

The time for fleet-spec Pintaras was over, and the Bluebird was positioned as a more upmarket and therefore more expensive vehicle. To that end, the base LX was pricier than even the flagship Pintara, with the range opening just $50 shy of $30,000.

Unlike the Pintara, which offered a choice of 2.0-litre and 2.4-litre engines, the Bluebird came only with a double overhead-cam 2.4-litre with 112kW of power at 5600rpm and 210Nm of torque at 4400rpm. This was mated with either a five-speed manual or four-speed automatic transmission.

Using a 2.4-litre, the Bluebird therefore slotted neatly between the 2.0-litre Pulsar and 3.0-litre Maxima.

The Bluebird featured four-wheel independent suspension, while even the base LX came well-equipped with power windows, central locking, cruise control, front cornering lights, alloy wheels. The more luxurious Ti added a sunroof, climate control, CD player and a six-speaker sound system and was auto-only, while the SSS featured a rear spoiler and fog lights. Unusually, however, there were no anti-lock brakes or a driver’s airbag on any model.

The SSS’ party trick was its standard head-up display, which projected information like speed, indicators and system messages onto the windscreen. This was the first time this technology had been offered in a car in Australia, though Nissan had first used the technology in 1989 and General Motors had narrowly beaten it to market with a HUD in 1988.

The Bluebird was targeted not against the wide-body Toyota Camry and Mitsubishi Magna, but rather against lower-volume Japanese imports like the Mitsubishi Galant, Mazda 626 and Ford Telstar.

As a vehicle produced in Japan, it was on the narrower side so it didn’t fall into a higher tax bracket there. At 1695mm, it was only 35mm wider than a Pulsar. It was also 55mm narrower than a Mazda 626 – more popular here, but a poor seller in Japan as a consequence of its higher taxation.

The Bluebird never did soar. Nissan had aimed for 400 monthly sales but even in its first full year of sale it fell short with just 3577 – vastly better than the Galant (850) but short of the 626 (4930). Sales fell to 2512 in 1995, and continued their downward trend.

That was despite a minor facelift in 1995 that belatedly brought a driver’s airbag, though at the expense of cruise control in the LX. In 1996, Nissan also slashed the base price by $1720, bringing it back below the $30,000 barrier after it had incrementally risen during its run.

The base LX’s price was now $500 lower than when it had launched. A price cut of this size was unusual in the mid-1990s, when Japanese cars were getting ever pricier due to an unfavourable exchange rate. But the U13 Bluebird was at the end of its flight globally, and it was withdrawn from Australia in 1997.

Perhaps its disappointing sales were a result of its fuddy-duddy name. Nissan Australia reportedly didn’t have money to market a new mid-sized name after shuttering its Clayton factory, leaving it with a pair of undesirable names to choose from: Pintara and Bluebird.

The latter had years of recognition, having once been one of Australia’s best-selling mid-sizers. But it was always a thoroughly unadventurous vehicle, which led Nissan Australia to take great pains in its advertising to point out this new, front-wheel drive model was like no Bluebird before. This didn’t appear to have worked, even though the revived Bluebird was a thoroughly competitive, well-built mid-sizer with contemporary styling.

When it came to the end of its life, Nissan had to make a decision. The second-generation Altima wasn’t available in right-hand drive, while the Japanese-market Bluebird was quite possibly the blandest thing on four wheels.

An unfavourable exchange rate soured Nissan Australia on the Japanese Bluebird even further, so Nissan looked to the UK.

The second-generation Primera was introduced in 1995 and was built at the company’s Sunderland plant in the UK. Like its first-generation predecessor, the new Primera was a conservatively-styled sedan, hatch and wagon, but one that had been tuned for the European market. That meant it handled well and was regarded as one of the most enjoyable mainstream vehicles to drive with a Japanese nameplate, though its largest engine was only a 2.0-litre.

Alas, rumoured plans to bring the Primera here never eventuated, and after the Bluebird was withdrawn in 1997 Nissan ended up going without a mid-sizer until 2013 when it introduced the Altima.

By this point, the Japanese-market Teana – which we’d known here for two generations as the Maxima – had been replaced with a Japanese-built version of the American Altima. We’d therefore skipped two generations of Altima until getting this one, but it wasn’t around for long – Nissan Australia axed it in 2017, and has been without a mid-sized sedan ever since.

What a difference marketing makes.

When the J30 Maxima arrived in the US in 1989, it was marketed as a “four-door sports car”. Nissan even slapped on 4DSC window decals.

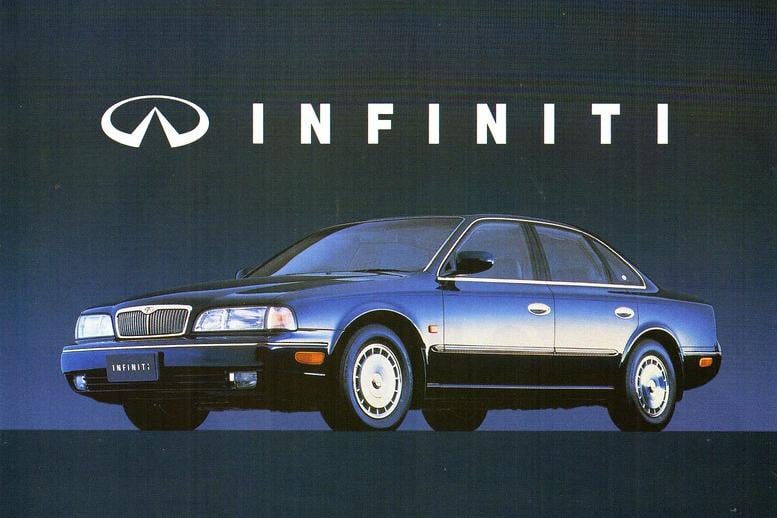

The J30 series (not to be confused with the unrelated Infiniti J30) was the third generation of Maxima, but it was the first to arrive here. Its role in Australia was as a premium, imported flagship, effectively taking the place of the stodgy Cedric-based 300C that had been axed in 1988 while also filling the void left by the locally-built Skyline.

Perhaps it was for that reason that Nissan Australia didn’t choose to market it as a sporty vehicle. There’d be no sporty variant or manual transmission, something offered every year during the J30’s run in the US. There, the SE trim level offered firmer sport suspension, as well as cosmetic tweaks like a rear spoiler and white-faced gauges.

Nissan continued marketing the front-wheel drive Maxima as a quasi-sporty vehicle in the US with the A32 redesign, launched for 1995. That was despite styling that was arguably blander, as well as the substitution of independent rear suspension for a less sophisticated multi-link beam axle.

Our A32 Maxima wouldn’t be a Maxima but, rather, a rebadged A32 Cefiro, its Japanese-market sibling that was sold in North America as the Infiniti I30. Styling was even more starchy than the North American Maxima, and yet Nissan Australia did something unexpected: it introduced it in 1995 with the option of a manual transmission.

This was available in base 30J and mid-range 30G variants, the latter featuring cruise control and a leather-wrapped steering wheel among other niceties. There was little direct competition – even the 30J manual was around $5000 more than a manual Toyota Vienta Touring, while a V6-powered manual Mazda 626 SDX or Eunos 500 was smaller.

It’s not as though the presence of a manual transmission was sporty on face – you could still get manual Magnas and Accords and the like, though the transmission was typically limited to lower-spec models. But it was an unusual move for Nissan, and sales volumes must have been low as the manual was gone by the end of 1996.

Nissan would briefly offer an ST-R version of the subsequent A33 Maxima, with side skirts, 17-inch alloy wheels and a rear spoiler. But it was the last time Nissan Australia tried to pitch the Maxima as anything remotely resembling sporty, with a comfort-first focus for its subsequent two generations which were based on the Japanese-market Teana.

While manual transmissions disappeared from the US Maxima in 2007, Nissan has continued to offer a sporty variant. Contrast that with here, where seemingly every Maxima was finished in beige with a tan interior and a tissue box behind the rear headrests…

Judging by how the market has been trending increasingly towards SUVs, Nissan Australia may have been ahead of the curve in culling its mainstream passenger cars and embracing a line-up consisting almost entirely of SUVs. However, there was a time when Nissan was a bit of a laggard.

Let’s rewind to the 1990s. Toyota had initially confounded buyers with its RAV4, which arrived here in 1994. “Wait a minute, you mean I can have SUV styling and car-like dynamics?” buyers asked, before quickly handing over their money.

The nascent crossover market quickly grew, with the Honda CR-V and Subaru Forester arriving in 1997. But Nissan was among the slower to offer a global model, with the X-Trail not arriving until 2001; that’s despite the brand having offered the funky Rasheen crossover in Japan since 1994.

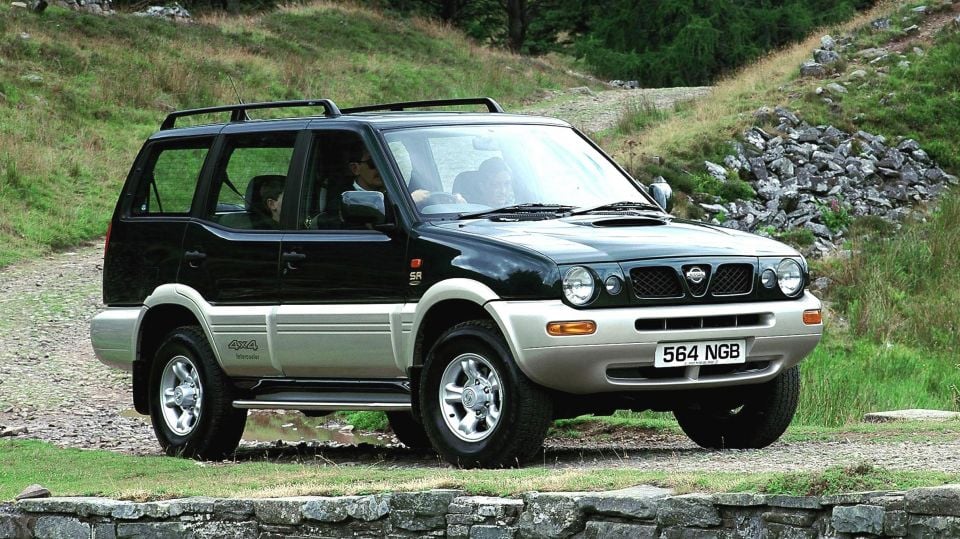

With buyers clamouring for these smaller, more road-friendly SUVs, Nissan Australia looked at the global product portfolio and secured the Terrano II to slot in underneath the Pathfinder. This Spanish-built SUV had been in production since 1993, and was also sold as the Mistral in Japan and as the Ford Maverick in Europe.

It had body-on-frame architecture and a live rear axle but dimensions slightly larger than unibody crossovers like the CR-V and RAV4, if smaller than the likes of the Mitsubishi Pajero and Holden Jackaroo. Price-wise, it slotted in between these two groups.

Its price made it Australia’s most affordable three-row SUV at launch. However, it was hamstrung by offering only a manual transmission with its 2.4-litre naturally-aspirated petrol and 2.7-litre turbo-diesel four-cylinder engines, while an eight-seater Toyota Prado was only around $3000 more.

The Prado may have been roughly the same length as the Terrano II and rode a similar wheelbase, but it was 65mm wider. Unusual styling penned by Ercole Spada at the I.DE.A Institute, also responsible for models like the Alfa Romeo 155, seemed to emphasise the Terrano II’s narrowness.

The bug-eyed look up front was unusual, and a step backwards from the inoffensive front end of earlier Terrano IIs not sold here.

Much as the Terrano II had been around for several years in Europe before it came here, it would go on to live for several years after it was discontinued here.

Axed in Japan in 1999, it was phased out in Australia the following year. We missed out on a third facelift that gave it a more butch, Navara-like front fascia, and Nissan Australia went without an entry-level SUV until 2001.

The Terrano II was indirectly replaced by the X-Trail, which gave Nissan a new entry-level SUV offering that simultaneously offered more rugged, handsome styling and unibody construction and a correspondingly more car-like demeanour on the road. Most importantly, it had an automatic transmission. The rest is history.

Being a top 10 list, we’ll always have to leave some vehicles on the cutting room floor. Here are just a few honourable mentions:

Take advantage of Australia's BIGGEST new car website to find a great deal on a Nissan.

William Stopford is an automotive journalist based in Brisbane, Australia. William is a Business/Journalism graduate from the Queensland University of Technology who loves to travel, briefly lived in the US, and has a particular interest in the American car industry.

Jack Quick

8.4

6 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

8.1

5 Days Ago

Max Davies

8

4 Days Ago

James Wong

8.1

3 Days Ago

James Fossdyke

2 Days Ago

CarExpert.com.au

2 Days Ago