Max Davies

2026 GWM Haval Jolion price and specs

6 Minutes Ago

Perhaps one of the most infamous badge engineering projects in Australian motoring history, why did Holden and Toyota work together and what did they make?

Contributor

Contributor

Australia in the late ’70s and early ’80s had a protectionist mindset, and the car industry was no exception.

To protect local manufacturing, the Federal Government introduced a 57.5 per cent import tariff, forcing the Big Five such as Toyota, Ford, Holden, Mitsubishi, and Nissan to build models locally.

Although a variety of vehicles was available, it was unsustainable in a small market with a population of only 15 million. Tariffs helped continue local manufacturing, but also insulated domestically-made vehicles from competition, ultimately hurting the customer.

Additionally, a lack of competition meant poorer quality, less innovative vehicles that bore limited export potential, reducing the potential revenues that domestic manufacturers could bring in.

The Hawke government came into power in 1983, and set about pursuing a more globalist economic policy that opened up Australia to international trade.

In accordance with this, Industry Minister at the time, John Button, decided to rationalise the car industry in the belief that it was better for local production to have a small slice of a large pie than a large slice of a small one.

In order to improve production efficiencies and produce export-ready cars at a lower price, Button introduced the Motor Industry Development Plan (known colloquially as the Button Plan).

Following consultations with local industry officials and trips to Japan to visit the headquarters of the major Japanese firms with a presence in Australia, the plan called for halving the number of Australian-made models from 13 to six.

To do this, local manufacturers jumped into bed together – and perhaps two of the strangest partners were Holden and Toyota. The Button Plan was launched in 1985, and by 1987 Toyota in Australia and General Motors-Holden had formed a joint venture known as the United Australian Automobile Industries (UAAI).

The primary purpose of UAAI was to share design and engineering resources, and effectively allow for the production of rebadged vehicles. Meanwhile, sales and marketing functions would be kept distinct to allow for some differentiation.

On paper, UAAI was a win-win for both companies. Holden’s range, as was the case during most of its history, revolved around larger models such as the Commodore, and so UAAI gave it access to reliable small and medium car options.

At the time, Holden also had a separate, engine-only export business. This business was successful and had earned the company ‘import credits’ it could use to sell vehicles made overseas without any import duties being levied.

It turned out Holden had a surplus of these import credits, and in return for Toyota producing rebadged models for Holden, Holden would give these surplus credits to Toyota, which could use them to more easily import models from its global portfolio such as the Land Cruiser, HiLux and Cressida.

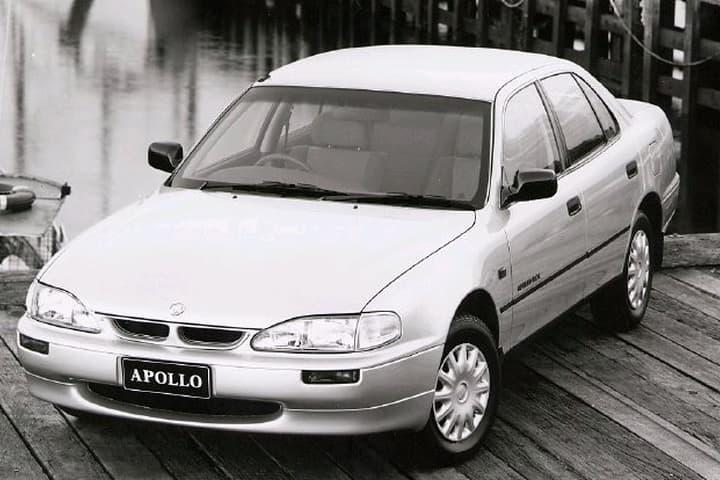

The formation of UAAI resulted in three badge-engineered models, namely the Holden Apollo (Camry), Holden Nova (Corolla), and the Toyota Lexcen (Commodore).

The Apollo was produced in parallel with the V20 and XV10 generations of the Toyota Camry, from 1989-1997.

An indirect replacement for the much-maligned Holden Camira, the Apollo was offered in Holden’s then-traditional trim lineup of SL, SLE, SLX and GS, with later models available with either a 2.2L 4 cylinder or a 3.0L V6 engine, producing 93kW and 136kW respectively.

With only minor cosmetic and detail differences between the Apollo and the Camry, later models had two options available, namely ABS brakes for $990 and air-conditioning for $2000.

One size down from the Camry at the time was the Corolla. Holden’s version was called the Nova. Produced and sold from 1989 to 1996, early models were available with 1.4 and 1.6L engines producing 60kW and 67kW respectively, before the addition of fuel injection in 1991 upped power 75kW for the 1.6L engine.

Later models in sporty GS trim were made available with a punchier 1.8L fuel-injected engine 85kW in both sedan and hatch variants.

In exchange for being able to sell the Camry and Corolla under its own brand, Toyota received access to the most popular product in the Holden portfolio, the Commodore, which was sold under the Lexcen model designation.

The Lexcen designation itself traces its origins back to Ben Lexcen, the designer of the famous winged keel yacht, Australia II, that became the first non-American boat to win the America’s Cup in 132 years.

A rebadged second generation Commodore, the Lexcen was sold across VN, VP, VR and VS guises and mirrored its donor car except for minor cosmetic differences.

It was available only with a V6 engine paired to an automatic transmission, unlike the Commodore which was available with both a manual and a more powerful V8 engine.

Despite Senator Button’s best intentions, customers were not fooled by the badge engineering program, and minimal differentiation meant sales of the rebadged models were paltry in comparison to their donor cars.

It’s estimated that in each case, the Holden Apollo, Holden Nova and Toyota Lexcen were outsold by a ratio of seven to one when compared with the original model. The poor sales and other differences led to the dissolution of UAAI by March 1996.

Holden replaced the Nova and Apollo with European designs from its sister company, Opel.

The Holden Astra was imported from Germany to replace the Nova, while it was able to assemble the Vectra locally to replace the Camry from 1998-99.

Meanwhile, Toyota replaced the Lexcen with the more upmarket V6 only Vienta (effectively a more luxurious Camry) and subsequently the Avalon.

Ultimately, the Button Plan did rationalise Australian vehicle production, but the focus remained on the manufacture of larger vehicles that remained difficult to export elsewhere.

Max Davies

6 Minutes Ago

Derek Fung

1 Hour Ago

Matt Campbell

8 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

24 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

1 Day Ago

Derek Fung

1 Day Ago