Jack Quick

8.4

5 Days Ago

LSDs, locking diffs and open diffs. Differentials have been a key area of innovation recently, but what do they actually do?

Contributor

Contributor

As a vehicle turns, the inside wheels travel a shorter distance than the ones on the outside. The fundamental problem a differential aims to solve is allowing the outside wheels to spin faster than the ones on the inside, and prevent them from being dragged along to keep up.

The differential consists of a series of gears connecting a car’s driveshaft (the shaft that transfers power from the engine) to a split axle. Apart from varying the speed of the wheels, the differential also works to split torque between them.

In an automotive context, the standard type of differential is known as an open differential. However, there are other types available including locking differentials, limited-slip differentials (LSD), and torque vectoring differentials, which will be covered in a separate article.

An open differential is the most basic type of differential and is found on non-performance cars today. It consists of three key components, namely the internal gearing, a ring/crown gear and a pinion gear.

The internal gearing comprises the gears allowing the wheels of the car to rotate at different speeds. Instead of a solid beam connecting the wheels, the axles are split into two halves, each capped with a gear. Another gear parallel to the axle then connects them.

The ring gear encapsulates the internal gearing assembly and connects it to the driveshaft via another gear known as the pinion gear.

Looking at buying a vehicle for towing or for heavy off-roading? You may want to consider its axle ratio.

This is the ratio of the number of turns that the pinion gear must make for each revolution of the ring gear. For example, an axle ratio of 3:1 would mean the pinion gear turns 3 times for 1 revolution of the ring gear.

Vehicles such as the Jeep Wrangler and certain utes and pick-up trucks (especially American options such as the Chevrolet Silverado and Ram 1500) may offer a choice of axle ratios. The higher the axle ratio, the greater the torque multiplication.

As a rule of thumb, this means that vehicles with higher axle ratios (assuming all else the same) have greater torque at lower speeds, and are therefore more suited to towing at the expense of a worse fuel economy and a lower top speed.

Alongside the ability to ensure wheels are able to rotate at different speeds, the key advantages of an open differential compared to the types detailed below lie in its lower weight, simplicity and cost to manufacture.

The primary disadvantage of an open differential is that at any time, it can only split the torque 50/50 between the wheels. This means that torque is still transferred to a wheel without traction, causing it to spin without moving the vehicle.

Locking differentials are able to ‘lock-up’ the internal gearing and other components of the differential mechanism so the wheels spin at the same speed across an axle.

Locking differentials are often used in off-road vehicles, with the primary benefit over its open counterpart being that up to 100 per cent of available torque can be directed to the wheel with traction.

For more information on locking differentials, see Paul Maric’s earlier article here.

A limited-slip differential aims to offer the best of both worlds, allowing for different wheel speeds across an axle, but also for a greater proportion of torque to be transferred to the wheel with more traction.

The three key types of LSDs are mechanical (clutch-based) LSDs, viscous LSDs and helical/Torsen (torque sensing) LSDs.

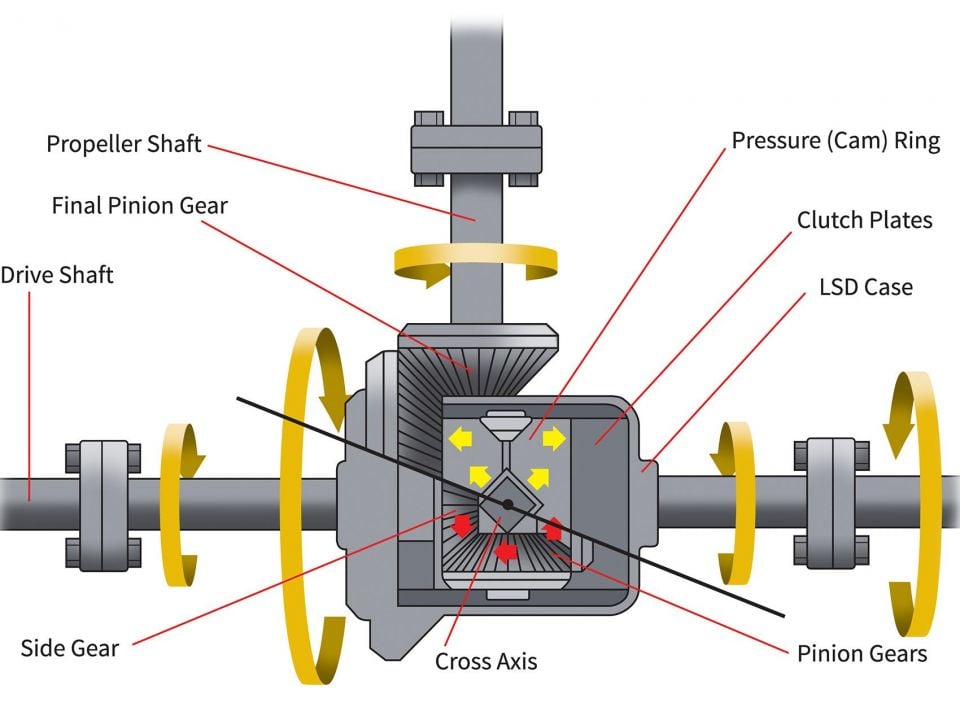

A mechanical LSD uses a clutch with multiple discs (also known as a multi-plate clutch) in combination with pressure rings and the pinion gear. If the vehicle is accelerating, the pinion gear exerts a force on the pressure rings, which cause them to lock-up the clutch discs through friction, thereby enabling greater traction for the wheels.

In a two-way mechanical LSD, the pressure is also exerted when the car is decelerating to provide greater braking stability.

An electronic LSD (eLSD) is a type of mechanical LSD where computers (rather than mechanical force from the pinion gear) can control the interaction between the clutch and the pressure rings for faster responsiveness to the vehicle movement.

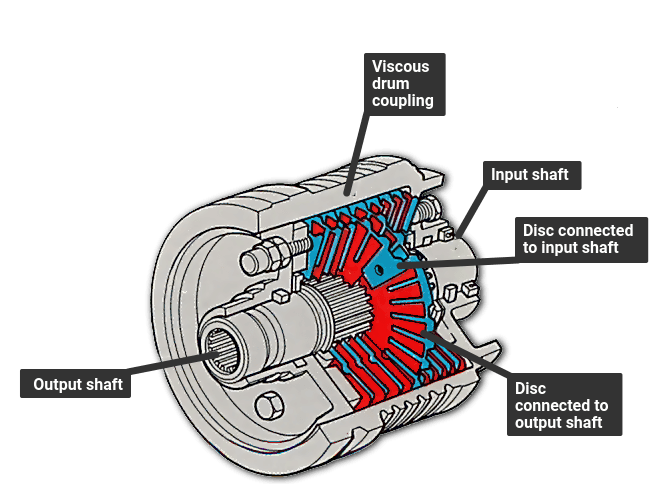

As the name implies, viscous LSDs make use of a viscous coupling where the multi-plate clutch is bathed in a thick oil (viscous fluid).

The fluid serves the same purpose as the pressure rings in a mechanical LSD. In the event that a wheel is spinning faster than its counterpart (e.g. on a slippery surface), the fluid acts as a source of friction, equalising the rotational speed of both wheels and replicating the effect of a locked differential.

Although a viscous LSD is smoother to operate and requires less maintenance than its mechanical counterpart, it cannot completely lock-up to direct 100 per cent of torque to the wheel with traction, as an initial difference in rotational speed between the wheels is required for the fluid to function.

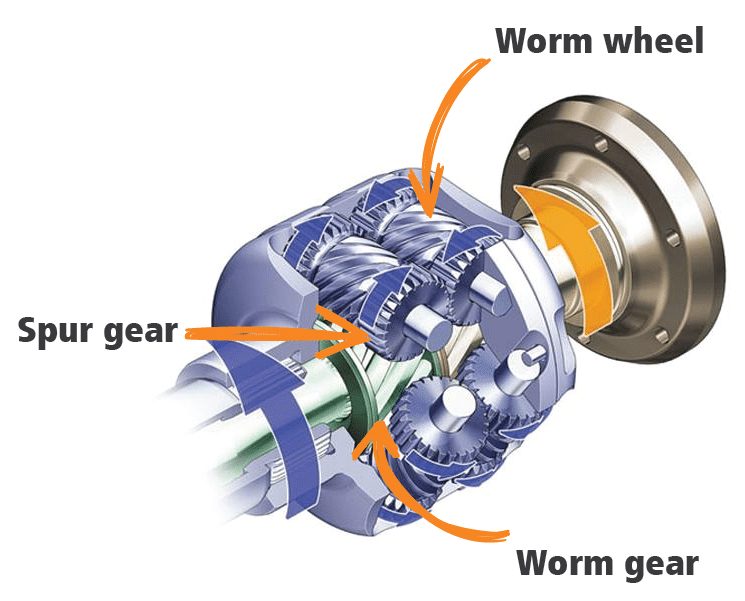

Torsen/helical LSDs are another type of LSD that, instead of using friction through pressure rings (which will eventually require replacement), use a set of worm gears to provide the necessary resistance to lock-up the internal gearing and thereby apportion torque between the wheels.

Apart from maintenance, the primary advantage of a Torsen differential is in its responsiveness. Unlike an ‘on-off’ mechanical LSD, the worm gear is always enmeshed with the internal differential gearing, greatly improving responsiveness.

Some examples of cars using various types of LSDs include the Mazda MX-5 (mechanical LSD in manual guise), Nissan 370Z (viscous LSD) and the Ford Mustang (Torsen LSD with the 2.3L High-Performance variant).

Jack Quick

8.4

5 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

8.1

4 Days Ago

Max Davies

8

3 Days Ago

James Wong

8.1

2 Days Ago

Marton Pettendy

1 Day Ago

CarExpert.com.au

1 Day Ago