Josh Nevett

3 Days Ago

So what exactly is e-fuel? How’s it made, how much does it cost, can you buy any of it right now, and is it going to save the world?

Contributor

Contributor

In the simplest terms e-fuel is a gasoline that’s made entirely from clean energy (wind and water in the case of Porsche’s version) that can be used in any internal combustion engine on the planet.

It requires no mining or burning of fossils to make but instead removes CO2 from the atmosphere during its manufacture, hence the reason Porsche refers to its particular brand as a ‘virtually carbon neutral’ fuel. For the planet, indeed, for all of us, that surely makes e-fuel very good news, does it not? Correct.

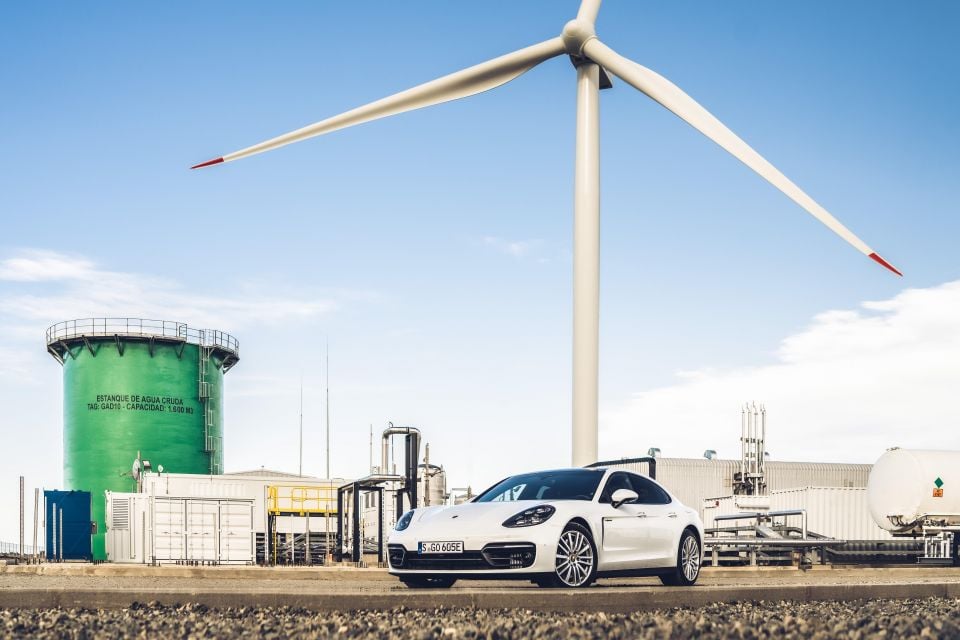

It’s made by splitting the hydrogen from the oxygen you get in plain old water (H2O) using a machine called an electrolyser that’s powered entirely by the wind, in Porsche’s case one that’s harnessed by a giant Siemens turbine at the southernmost end of Chile, where the wind blows very hard, all the time. We’re talking here about the Straights of Magellan and the once notoriously perilous-to-negotiate Cape Horn.

The hydrogen that’s harnessed from this process is then mixed with CO2 that’s extracted from the air by a radical new process called ‘air capture technology’ to create e-methanol.

This e-methanol then goes through a final process called MTG (methanol to gasoline) that’s been developed by Exxon-Mobil, at the end of which raw 93 octane fuel is produced. This can then be brought up to whatever octane rating you require with final additives. And not a single fossil is set fire to during the entire process.

The resulting e-fuel can be used in anything from a Rover V8 car on carburettors to a Porsche Panamera Turbo S to a commercial passenger jet. It’s that flexible in its potential usage.

In cars that emit less than about 100g/km it’s actually closer to being carbon negative rather than carbon neutral because the CO2 that’s removed from the atmosphere during manufacture very nearly outweighs the amount of CO2 that’s emitted when it burns. So in theory that makes e-fuel a very big win indeed.

But inevitably there are caveats. For starters, it costs a crazy amount of money right now, mainly because there isn’t any of it in circulation yet. The shiny new plant I visited recently in Chile – the first of its kind anywhere in the world – can produce a mere 130,000 litres of e-fuel in one year alongside 350 tons of e-methanol. So at the moment the notional price of £40-45 ($72-81) a gallon is a bit ridiculous because you can’t actually buy any of it. Yet.

But as with any commodity, price is always relative to supply, and the whole idea of Porsche’s involvement with e-fuel is not to make or sell the stuff – it makes and sells cars, not fuel – but instead to be the charismatic front man for a technology that, in truth, is being financed and developed by the same energy companies that have trousered billions over the years making conventional fuels.

The main financial stake in the Porsche plant (which is run by Highly Innovative Fuels Global – HIF) has been put up by a Chilean mining company called Andes Mining Energy, while the most expensive piece of technology within the plant itself – the MTG system – is provided by Exxon Mobil. So in some ways e-fuel is much like conventional fuel but remade cleanly, then remarketed with a sexy new Porsche badge on the barrel.

Yet whoever makes it, and whichever companies end up earning the most money out of it, e-fuel has to be embraced as a good thing overall. A very good thing if Porsche succeeds in managing to persuade the world’s law makers en masse to legislate for, rather than against it, in the short to medium term.

Because what Porsche is trying to say here is; look folks, we can’t afford to ignore this technology any longer because for the next 15-20 years, the internal combustion engine is here to stay, like it or not. And right now the infrastructure for widespread electrification is not there globally, and won’t be there realistically for at least another decade, possibly longer, which means there’s a huge time-gap that needs plugging if we’re truly going to become a carbon neutral world by 2050.

After all, it’s estimated that well over a billion ICE vehicles will still be on our roads by 2030, and will still require fuel to run on – but if they run on e-fuel rather than conventional gasoline then far, far less bad stuff will end up in the atmosphere between now and then.

And in case you’re still wondering, it’s not what comes out of the tail pipes that’s the problem. It’s the process of making the fuel that powers our cars, planes, trucks and ships that’s the real issue. The key difference is (as already intimated) the manufacture of e-fuel is clean; the production of conventional gasoline is anything but.

Ultimately a vehicle will emit the exact same amount of CO2 running on e-fuel as it will on traditional fuel, and it’ll consume the exact same amount of fuel, too. Same g/km and L/100km numbers. But the creation of the fuel in the first place is where we’re going wrong.

E-fuel, synth fuels, bio-mass fuels – call them what you like, they all end up with a broadly similar result – are surely a major part of the short to mid-term answer. Porsche’s main claim to fame with its e-fuel is that it’s faster and easier to scale-up and produce at an industrial level.

For anyone who fancies running a classic car all-but guilt-free in 20-30 years’ time and beyond, e-fuel could be a far longer-term solution. If they really take off they could be usable and affordable virtually forever.

And maybe the best news of all is that, finally, our law makers might just be beginning to see sense, too. On March 2 the UK’s Transport Select Committee published a paper strongly advising the government to do whatever it can, as quickly as it can, to speed up the mass production and use of e-fuel in the car and aviation industries, plus take a good long look at how e-fuels can be adopted to work in haulage and shipping at the same time.

It’s not a watershed moment but it shows that our decision makers are at least listening to people who know what they’re talking about.

Ultimately that’s what Porsche’s involvement with e-fuel is all about; getting politicians and global industry to wake-up, listen, and hopefully to do the right thing, right now, before it’s too late.

Could e-fuel save the word? Not on its own, no. But it’s a damn good place to start, because we’re almost out of options otherwise.

So what does it feel like to drive a twin-turbo V8 Panamera that’s running on Porsche’s e-fuel – the same, different, better or worse than the same car running on regular unleaded?

Well once I’d done a tour of the plant in Chile and been bamboozled, stunned, impressed and downright petrified by the science behind it in equal measure, Porsche handed me the keys to a Turbo S and invited me to drive it along the famous End of The World Road, having filled it with 50-litres (so approximately $500) of e-fuel. So I then drove it for several hundred miles.

The scenery was incredible, the roads endlessly long and straight, and not very well surfaced for much of the time. I saw Pumas and Condors (seriously) and drove for hours on end across some of the bleakest, most beguilingly untouched landscapes you could ever wish to visit.

Every time I stopped for a comfort break or just to get out and take a good look around, the door of the Panamera would be flung open violently on the wind. Because it’s there all the time, it never ceases.

It’s the very reason why Porsche and HIF and Exxon Mobil and all the other investors in e-fuel have alighted here in the first place – to harness the power of a wind that never goes away.

And unless they’re all fibbing collaboratively on truly a grand scale, it works. The Panamera drove identically on the e-fuel it had been filled with on day one at the plant to the way it did running on the conventional unleaded it was topped up with hundreds of miles away on day two. There was zero difference.

That felt like a major realisation at the time but only because there was no perceptible change. Same fuel consumption, same emissions, same feel to the throttle, same car.

Except on day one the Panamera ran on a fuel whose manufacture had already taken out most of the CO2 which its V8 then put back into the atmosphere, and on day two it was a one-way street.

That’s a potentially life-altering difference, one that could mean it’s still possible to execute a U-Turn and alter our trajectory even at this late stage, even on the Ruta del Fin del Mundo. Assuming, that is, our rule-makers and big industries – all of us, to be fair – are prepared to compromise a little and, for once, do the right thing.

We got ourselves into this mess in the first place, after all. Now it’s up to us – and them – to put things right. And e-fuel is most definitely part of the solution.

Take advantage of Australia's BIGGEST new car website to find a great deal on a Porsche.

Steve Sutcliffe has been a motoring journalist for over 30 years, formerly serving as editor of Autocar. He’s also a successful racing driver, finishing second in his first ever car race driving a Caterham at Silverstone.

Josh Nevett

3 Days Ago

William Stopford

3 Days Ago

James Wong

1 Day Ago

Andrew Maclean

19 Hours Ago

Max Davies

11 Hours Ago

Derek Fung

9 Hours Ago