With car theft remaining an increasing national issue, newer cars are no longer safe from thieves.

We wanted to see just how easily thieves could steal a new car today by engaging a locksmith to demonstrate some of the tools readily available on the internet today.

We engaged Chamara, the owner of Brisbane-based Tapsy Locksmiths, to demonstrate the tools available to anybody on the internet and shot a video showing how the process works.

We’re revisiting this article, which was originally published last year.

We’re not writing this story because we want to teach people how to steal cars. All of the tools Chamara used for this experiment are legal tools that Chamara legitimately uses for his business.

However, these tools, according to Chamara, can be purchased by virtually anybody on the internet. And you can imagine how easy it would be for these tools to fall into the wrong hands.

That’s why we’ve gone to lengths in the video to conceal anything that reveals the website or the tools that Chamara uses.

Background

To begin, let us provide some context. When accessing a modern automobile, one typically employs either a traditional key with a central locking system or a proximity-sensing key, which remains in the user’s pocket while they activate the vehicle’s lock.

In most instances, even if a car utilizes a proximity-sensing key, a physical key is embedded within the key fob. This is to ensure manual access to the vehicle if the proximity key’s battery becomes depleted. The physical keyhole may be concealed behind a plastic covering or other decorative element.

An exception to this rule includes vehicles like Tesla, which rely solely on RFID-enabled cards or smartphones for access.

Nevertheless, Teslas are equipped with a manual front bonnet release situated behind the bumper in case the battery fails. Within the bonnet, there is a mechanism for providing power to a 12V battery, which subsequently permits authentication with the car.

The physical key concealed within a key fob or the one used for the ignition, such as the example from the Hyundai i30, possesses a relatively distinctive cut pattern. This uniqueness, however, is not absolute, as multiple versions of the same key may exist worldwide.

Consequently, it is plausible that someone in another part of the globe possesses a physical key identical to yours, capable of accessing your vehicle. Nonetheless, these instances are generally restricted by region, making it improbable for vehicles within your area to share the same key profile.

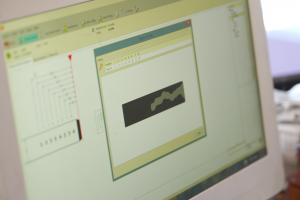

This specific key profile is assigned a “Key Code.” Locksmiths employ this Key Code in conjunction with key cutting machines and decoding software to create an accurate replica of the key, including its ridge profiles.

The Key Code also informs the locksmith of the required key type, as certain keys have cuts on one side, while others feature cuts on both sides.

Apart from the Key Code, locksmiths utilize a variety of electronic devices to encode new car keys.

The process differs among manufacturers and car brands. Some only necessitate a basic PIN code, whereas others mandate the installation of new firmware before encoding a key for the vehicle.

Regardless of the method, executing this procedure outside of the manufacturer’s domain typically demands third-party hardware. Often, this hardware incorporates a decryption mechanism that utilises the vehicle’s existing algorithm to access the car’s electronics based on its unique Vehicle Identification Number (VIN).

Getting into the Hyundai i30

It is not uncommon for manufacturers to charge exorbitant fees, often in the range of hundreds or even thousands of dollars, for authentic keys and programming services.

Locksmiths, such as Tapsy Locksmiths, can provide these services at a fraction of the cost using aftermarket or, in some instances, genuine OEM keys, which they can program themselves or instruct the customer to program through the manufacturer.

For Hyundai vehicles specifically, it is surprisingly straightforward to both cut a new key that works in the door and program a new key within seconds of accessing the car.

Chamara demonstrated a website that, when provided with the vehicle’s VIN, generates the Key Code and PIN code for the car. While this website is ostensibly intended for locksmiths only, Chamara noted that the verification process for access was rather lax.

Chamara proceeded to work on an i30, utilizing the vehicle’s registration number (which could be easily obtained by a thief) to retrieve the VIN from the Queensland registration office.

After entering the VIN into the website, he obtained the Key Code and PIN code, which he used to cut a new key identical to the one in the owner’s possession.

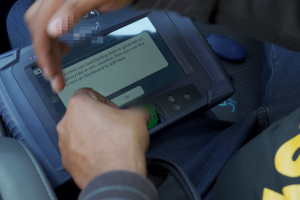

He then proceeded to the vehicle with the electronic device required for key programming. Upon using the newly cut key to open the door, the alarm was triggered. Chamara connected his electronic device to the OBD port and entered the PIN code from the website, promptly deactivating the alarm.

It is worth noting that when a car alarm is activated, most people do not investigate immediately, typically waiting until the alarm has persisted for a few minutes.

Chamara managed to disable the alarm within 10 seconds of gaining access to the Hyundai, making it unlikely that anyone would pay attention to the brief alarm activation.

After entering the PIN code, Chamara programmed a new key for the vehicle using a blank key. This new key disabled the car’s immobiliser, allowing him to start the engine with the freshly cut key.

In under a minute, Chamara was able to access and potentially drive away in a Hyundai i30 that had been inaccessible just moments before.

Getting into the Toyota Kluger

How about a brand-new Toyota? Chamara informed us that the company had updated its security system in recent years.

Previously, stealing a new Toyota was as easy as stealing a Hyundai, but it became more challenging with the new security measures. However, last year, the updated security system was compromised, leading to the development of a third-party tool designed to bypass the system.

The procedure for the Toyota initially paralleled that of the Hyundai. First, a key for the vehicle needed to be cut, which Chamara accomplished using the VIN obtained via the registration and the Queensland registration website.

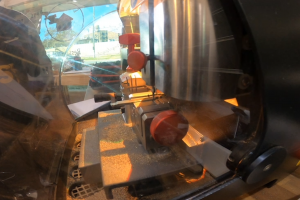

Upon accessing the car using the keyhole on the door, the alarm began to sound. Chamara then employed a different electronic device that connects to the OBD port and an intermediary adapter linked to another security module. With this setup, he managed to write new firmware to the car, enabling it to recognise a blank key as the authorised key fob.

Subsequently, he instructed the car that all existing keys were lost, and the blank key fob communicated to the car that it was permissible to create new keys in the vehicle’s key database. After programming these new keys using the device, the car could be started and driven away.

The entire process took approximately 2-3 minutes. As with the previous example, the alarm was activated upon opening the door but was swiftly deactivated once Chamara authenticated with the car.

How to protect yourself

An increasingly prevalent method employed by thieves involves the use of relay devices.

In this approach, one thief aims the relay device at the front door of a residence, where proximity keys are often left. The device then transmits the key’s signal to an accomplice near the driver’s door of the vehicle. Consequently, the car perceives the key to be present, allowing the thieves to unlock and start the vehicle.

While they would be unable to restart the car without the key, the thieves could utilize one of the devices demonstrated by Chamara to reprogram a new set of keys at a remote location.

To protect against such relay attacks, consider purchasing a small Faraday bag for storing car keys at home, which prevents the key’s signal from extending beyond the bag’s interior lining.

In the absence of a website for obtaining a Key Code, criminals may resort to a turbo decoder. This tool inserts into a keyhole and, within 15 seconds, retrieves the lock’s inner key profile, enabling the thief to unlock the door as though they possessed the actual key.

Once again, thieves can employ electronic devices accessible to locksmiths to program new keys and abscond with the vehicle.

How can one prevent unauthorised access to the OBD port for key programming? Unfortunately, there is no simple solution. Disconnecting the OBD or disabling access to it entirely may provide some protection, but the OBD would be required for future mechanical diagnostics.

A more effective deterrent involves reverting to traditional security measures, such as purchasing a steering wheel lock. While a thief may succeed in programming a new key, they would be unable to steer the vehicle once it is started, thus thwarting the theft attempt.

CarExpert’s take

It is genuinely alarming to discover the ease with which a brand-new car can be stolen in today’s world. This vulnerability becomes more understandable upon closer examination.

For instance, in the case of the Hyundai i30, which was released in 2016, the vehicle would have been in the prototype engineering phase for years prior. The security system chosen for the car may have already been a couple of years old by that time – let’s say, from 2014.

Fast forward to the present, and the security system is nearly a decade old, providing ample time for malicious actors to decipher the encryption and identify entry points.

A potential solution to mitigate such threats involves over-the-air security updates that can adapt the security mechanism as needed. However, this may be challenging to implement for cars relying on keys or proximity devices utilising outdated technology.

Tesla appears to be on the right track by exclusively allowing phone or RFID access to their vehicles. This approach enables the company to deploy security updates as vulnerabilities emerge, providing a more robust defense.

Unfortunately, most legacy security systems in other vehicles on the market are essentially obsolete as soon as the cars are sold. This pressing issue warrants attention and action to protect both consumers and manufacturers.