Jack Quick

8.4

5 Days Ago

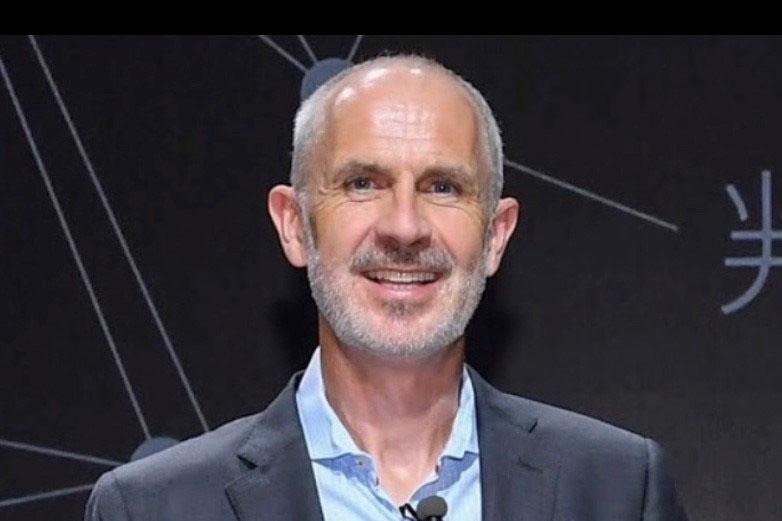

We talk with Volvo Cars CEO Jim Rowan about what he's bringing to the car business, and why it's ultimately all about 'software and silicon'.

Senior Contributor

Senior Contributor

Scotland-born Jim Rowan took over as Volvo Cars CEO and president in March 2022, to oversee its transition to a fully electric and largely software-driven carmaker by 2030.

Before this, his most high profile role was as CEO of cult consumer electronics giant Dyson, between 2017-2020 – which happened to be the period when it was developing its now-cancelled EV project.

Running a maker of chic vacuums is not your typical path to the top of a car company, with management usually dominated by people who’ve accrued decades of industry experience.

Yet as ‘car companies’ turn into ‘mobility companies’ and focus more on batteries, chips, autonomous driving, direct-to-consumer retail and software services, traditional skill sets may no longer suffice. Volvo’s parent Geely clearly thinks so.

As part of getting his head around the car business and Volvo in particular, Mr Rowan is spending time in what he calls the “extremities” of the globe, with Australia one of these – a market where Volvo just posted all-time record annual sales and promises to sell only EVs from 2026.

MORE: Volvo sold more EVs than ICE cars in Australia last month

We wondered what made Mr Rowan so keen to join the iconic Swedish car brand, what his uncommon pathway to leadership brings to the role, and what decisions he considers most important.

“Obviously I don’t come from that industry per se. I think one of the most important things is, especially when you take on a new role and you take on a new industry, really trying to understand what that industry’s about,” he said to get the ball rolling.

“We have about 42,000 people in the company. A very high majority of them really understand automotive, so I think it’s time for us to start bringing in some other things beyond automotive as the industry goes through this change.

“The reason I joined Volvo is pretty simple. Three reasons really. It’s a fabulous brand, I grew up with Volvo, I think it’s got a real authenticity, it’s a brand that kind of stands for something.

“I think it’s got a real authentic soul, and we see how that’s manifested over the years: the invention of the three-point seatbelt, but then the courageousness to actually give that away as an open patent for me talks to the kind of company that I like to work for.

“So that was a big factor for me in terms of joining the company: the actual brand itself and what it stood for.

“And then you’ve got this really interesting – I’m an engineer – [experience] as you go through massive transitions in industries, and we’ve got a double-headed transition going on right now in automotive.

“On one side you’ve got the technical transition, which is from petrol to electric propulsion and from-people driven to autonomous-driven vehicles – all the software, electronics, lidar, radar, cameras, sensors, code, computer technology, everything’s getting poured into that at the same time. And as an engineer, that’s just an interesting space to be in.”

The other side Mr Rowan discussed is the industry’s shift towards sales channels controlled by car-makers keen to directly engage with buyers more, and rely on franchise dealers less. Volvo is experimenting with a direct-to-buyer model in the UK and Sweden, but has no current plan to follow its Polestar brand (which it owns 48 per cent of) down this path in Australia – yet.

“At the same time, you’ve got this other transition, which is direct-to-customer and building a relevant e-commerce engine that can connect directly with the end customer,” Mr Rowan said.

“Not being from the industry, it seems actually quite strange to me that you can sell a 40, 50, 60, 70 thousand dollar product to a customer and never speak directly to that customer. People walked into the [franchise] dealership, bought the car through the dealership, and then all the service and the interaction and connection was through the dealership.

“And now I think the demographic is changing because of the way people shop online, and the way people expect to connect directly with the OEM that produces the product. A great example of that, of course, is Apple,” he added, though Tesla would be another.

“So that double, heavy transition of technical and commercial, and of course everything [being] underpinned by the genuine move towards sustainability,” Mr Rowan added, is what he saw as key factors behind his desire to enter the car industry.

“We were I think one of the first, let’s call it ‘traditional’, car companies that said ‘we’re going all electric’. We’re going to be a full electric car company by 2030. We’ll be halfway there by 2025. There are no ifs, no buts, no maybes, that’s it. We went out on an IPO on that message. We took people’s money from the market to say ‘this is where we are taking our company’.

“It’s starting to look more obvious now, but when the team who made that decision – which predates me, so I can take no credit for that – that team basically said, you know, ‘we’re all in here. This is the direction of travel and we think we should go there’.

When asked to expand on what his specific skill set can bring to the company at such a period of flux, Mr Rowan again pointed to the fact that Volvo isn’t short on car people, but may be short on people with a broader technology and customer experience background.

“We have 42,000 people in our company, I’m gonna say 41,500 people really understand automotive. I think we have it covered is my honest answer to that, and not just junior people, but a lot of senior people who have been in our company for a long, long time,” he told us.

“What we don’t have fully covered is, what’s this going to look like in five years time? What does the thinking look like in five years time?

“Because I come from the tech sector, I was amazed when I came into the auto industry just how much of the IP and the technology had been outsourced from the big car companies. They outsource it to what’s called the tier one guys,” he said, alluding to massive suppliers such as Bosch, ZF and Nvidia.

“So you take the traditional model of designing a car: you go to the big tier ones, you say ‘hey I need an electronic control unit for the lights and the brakes and this and that’, and they say ‘okay we will sell that to you, this is the cost, we choose the silicon, we choose the software and you plug and play’.

“Tesla came in of course and said, ‘no, we want to do core computing technology’. And that was the first time anything really different had been done in a long time.

“So I’ll summarise it by saying, the big profound changes in the industry that the industry’s now moving towards, which I think I can help bring [about] from the tech sector, as I understand software and understand silicon, and in tomorrow’s world of next generation mobility, if you don’t understand software and silicon already, you’re already in trouble.

“The problem is when you go through these transitions, it looks like the transition’s going to be linear because it’s 5 per cent [gains] a year and then boom, it hits the inflection point and the gradient goes up, and it goes really quick.

“The big issue is if you wait for the inflection point before you make the investment, it’s too late. And there’s a lot of companies saying ‘I’ll wait until until electrification becomes fully mainstream and I’ll invest’. You know what, buddy? You’ve just lost another market. It doesn’t work like that.

“You see it in smartphones. I was in the smartphone industry for a long time [Blackberry].”

“… It won’t be as profound a change in the auto industry. But this theory of the oligopoly as it goes to next-generation technology will play out. And by 2025, 26 the winners will be the winners, and a lot the other people who haven’t invested in the technology won’t have the IP and they’ll be back to where they were, which is buying the IP off of some other tier one to try and remain relevant.

“And that’s why we are investing in the core computers. That’s why we’re investing in batteries [Volvo has a JV battery plant in Sweden with Northvolt]. That’s why we’re investing in our own e-motors. That’s why we’re investing in our own inverters. That’s why we do our own battery management system.

“But it’s also why we are very choosy over what we buy versus what we build.

“Take infotainment. The Qualcomm Snapdragon processor is a pretty good processor, used in the majority of cell phones. Qualcomm know how to make silicon, we don’t need to be involved in that. We need to understand silicon, but we don’t need to have a fab and make it.

“I’m also very happy because, of 7 billion people on the planet, 5 billion have got either an iPhone or an Android, so I think they’ve kind of got that covered in terms of infotainment. I don’t really don’t care whether they say ‘Hey Siri’ or ‘Hey Google’, I don’t need them to say ‘Hey Volvo’, what does that really add?

MORE: Polestar 3, Volvo EX90 to use Google HD Maps

“… Android and Apple will continue to make massive investments in those platforms because they want it to remain relevant. So that’s another ‘buy’ for us. And then we go all the way down to silicon, and we are buying them from Nvidia. We don’t make our own SoC [system on a chip], I don’t think we need to.”

Mr Rowan went into detail on the evolving computational power of chips and how Volvo plans to stay in its lane as they improve, with 2025 iterations expected to be capable of a staggering 1000-1200 TOPs (trillions of operations per second, or tera operations per second).

“That’s as much computational power as anybody needs. Our job now is to take that computational power and do something meaningful with it,” he said. “And that is done through the software stack,” he added, referring to Volvo’s next iteration of ADAS safety systems.

“Sorry, I know that was a long answer to a short question… I should just have said software and silicon, done!”, Mr Rowan added.

This year will see Volvo launch the new EX90 large electric SUV – the safest and most computationally advanced Volvo ever – and the all-new EX30 small electric SUV.

MORE: Geely releases 2022 sales figures, Volvo and Polestar EVs up

Take advantage of Australia's BIGGEST new car website to find a great deal on a Volvo.

Jack Quick

8.4

5 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

8.1

4 Days Ago

Max Davies

8

3 Days Ago

James Wong

8.1

2 Days Ago

James Fossdyke

1 Day Ago

Alborz Fallah

1 Day Ago