Josh Nevett

CarExpert's top five mid-size SUV reviews of 2025

3 Minutes Ago

From show-car stunner to dealership darling. This series takes a look at the life cycle of a car from concept to development and facelifts in-between. This week, the concept phase.

Contributor

Contributor

It’s a familiar story. Carmakers let the designers loose on a concept, and it wows the motoring world with wild styling and clever new ideas.

Then it hits production, and we all wonder what went wrong in the transition from show car to showroom. It makes you wonder, what’s the point of concept cars?

Besides acting as a palette cleanser for designers tired of shaping economy cars, they allow carmakers to show the world a car’s purpose in its purest form.

Concepts serve to distil the essence of the idea behind the car. This could be its overall form, or it could give an insight into the specific design, technology, or performance the final vehicle may have.

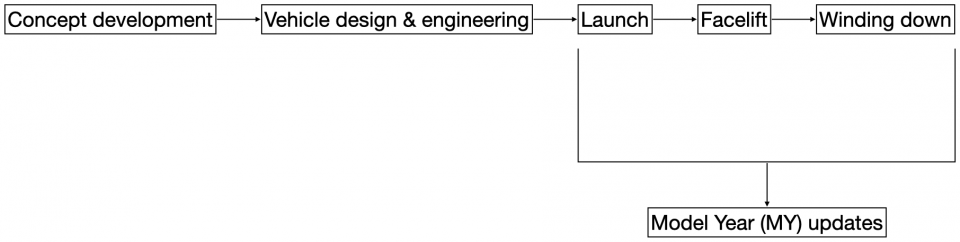

As evident in the diagram below, concept cars form the first phase of automotive product development, and embody the strategy behind the vehicle. Concept creation and the activities associated with it can start between three and five years before a car hits the showroom.

Designers, clay modellers, and other craftsmen aren’t the only people involved in creating a concept. They might be responsible for actually penning the concept, but plenty of departments work on concepts behind the scenes, including engineering, marketing and finance.

Personnel from these areas are responsible for creating a business case for a future production version of the concept. That takes into account broad-scale research into existing and future consumer trends, as well as upcoming regulatory changes such as new emissions standards or tightening safety requirements.

On a more focused level, they typically also include an in-depth analysis of the market segment the production vehicle will inhabit, including existing competitors, their market share, and whether the segment is growing.

Research into all of these fields helps the carmaker establish guidelines about how to price the vehicle, as well as characteristics such as performance, size, features, and the technology to include in the final car, well before substantive engineering and development has begun.

Once these background studies have set the goalposts for its development, a motor show is where the concept is typically unveiled.

Traditionally, the automotive industry as a whole comes together and holds these motor shows throughout the year – although their role is changing. They give carmakers a chance to showcase concepts alongside their existing range.

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, however, the future of the motor show is in doubt, with many carmakers hosting their own separate events, often online and streamed via YouTube.

Nevertheless, revealing a concept car, either at a motor show or online, allows carmakers to judge what is known as the VoC (Voice of the Customer).

This is industry jargon for initial customer feedback, and covers issues such as whether the concept has met customer needs and expectations. Questions such as whether the design is desirable enough, or whether the functionality is adequate are also asked at this point in time.

Of course, for product planners, designers, and others involved in the concept phase, the VoC feedback isn’t the sole determinant of whether the concept has been successful. Customer feedback is inherently backwards looking – and it’s none other than Henry Ford who is commonly attributed to have said “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses!”.

All of this is assuming that the carmaker is serious in bringing a version of the concept to production. Whilst this may appear to be an obvious assumption to make, it isn’t necessarily true, as discussed below.

Concept cars can largely be classified into three categories, namely the absurd and fantastical, statement design expressions, and more commonly, future production vehicles. As amazing as it would be, not every concept car is feasible for production.

The BMW GINA concept, revealed in 2008, is an example that clearly fits within the absurd and fantastical category. A roadster with an elastic fabric skin rather than a hard metal or carbon fibre body, the GINA was clearly never intended for production – there would be no way the fabric skin would pass safety and durability tests, for one.

That doesn’t mean it was a pointless exercise, however. Concepts that are ostensibly absurd can demonstrate the what a carmaker can do when the bounds of reality are released. More pragmatically, at a crowded event or motor show, they help put a spotlight on the brand, which in can generate media attention for regular production models in the carmaker’s range.

Design expression concepts, in contrast, are usually more realistic than absurd. Nevertheless, they may not make production as a complete vehicle. Instead, they may be used to establish a design language, elements of which (watered down, usually) will make it into a carmaker’s production vehicles.

The Polestar Precept concept is a great example of this. The Precept itself is unlikely to make production, but elements of the design, such as the grille and light design, and the materials used in the interior, will feature in future Polestar cars.

This makes sense given Polestar’s origins as a new electric vehicle marque attempting to establish an identity that further differentiates it from Volvo.

Mazda is another brand which loves to use design expression concepts, typically to mark new eras in its design language. The Vision Coupe Concept demonstrates the Kodo design philosophy, with its use of smooth surfacing to highlight light and shadow, and create a focus on proportion.

Elements of this design language have now been applied to the Mazda 3 and CX-30.

The most common class of concepts, however, are those directly previewing production vehicles.

In most cases, including the C-HR, the production version is toned down for reasons of cost, ease of manufacture, or safety and practicality, whilst retaining the essential themes of the original concept.

The Lexus LC is perhaps one of the few examples where the production model looks just as good, if not better, than the original concept.

Josh Nevett

3 Minutes Ago

Max Davies

33 Minutes Ago

Derek Fung

2 Hours Ago

Max Davies

8 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

16 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

17 Hours Ago