A Melbourne company that buys old Land Rovers and converts them into electric vehicles (EV) has moved into a new workshop near the city’s trendy inner west, and hired a former senior JLR and Holden quality controller.

The company is called Jaunt, and is the brainchild of Dave Budge and Marteen Burger. The former spent decades in digital agencies, the latter in advertising and production, but both have now turned their hands to a passion project.

The goal is to “up-cycle” these old paddock bashers and repurpose them for a second life, to make them appealing to the kind of buyers who’d probably shudder at the thought of driving one in its original incarnation.

Last time this writer caught up with the Jaunt team was before the COVID pandemic brought Melbourne to a halt. At the time they were based in the northern suburb of Coburg and were road-trialling a green two-door Series Land Rover conversion nicknamed ‘Juniper’.

They’ve since shifted to a bigger (but still cosy) site in the industrial section of Williamstown, and taken on a few more staff. Operations got back underway in earnest around October of last year.

They say the company learned a few sage lessons from the Juniper car, and applied them to their latest blue long-wheelbase prototype which at the time of writing, had just received road registration.

That car is soon destined for a new home at a Jervis Bay winery, which has decided to buy the vehicle as a promotional tool and hire-car for guests.

Jaunt says it has five vehicles on the go right now, in various stages of conversion, and all are spoken for. Three of these are classic Series Land Rovers, and two are Defenders.

This workload is expected to keep the 10-person team – which includes a former boat-builder, former navy marine engineer, and former industrial designer – busy until the middle of next year, though the goal is to speed up build times by introducing bigger OEM-style practises.

Jaunt hired Rob Davies to lead this. Davies was a product development quality manager on Holden’s VF Commodore program, and after that moved to the UK to be a plant team manager and architecture quality manager at Jaguar Land Rover, based in Solihull.

His remit covered vehicles like the Jaguar F-Pace and XE, and Range Rover Velar.

The challenge, he says, is dealing with smaller volumes here. At JLR or GM you’re buying hundreds of thousands of parts and you’re building from scratch, whereas at an EV converter in a warehouse, there’s a much more personal touch.

The goal now that the blue proto car has met VicRoads requirements is to formulate “standardised production” with both the Series and Defender models by late 2021, at which point the build times can theoretically be upscaled.

They’re designed to look like fully restored originals, with sandblasted and painted panels, and an interior that you can still clean out with a hose. But what makes up the guts of these classic EVs?

The blue LWB Series Landie actually uses batteries sourced from a written-off Tesla. Indeed, there are cratefuls of Tesla batteries in the warehouse, and the company considers these units to be the best in the business for now. They’re not sourced from Tesla, but from a third party dedicated to repurposing them.

“Long-term it isn’t ideal to have salvaged components but they’re still the best energy density,” co-founder Budge reckons.

Two Tesla modules fit so nearly into the Landie’s chassis rails that it’s uncanny. There’s room for 14 all up, and in the prototype there’s 42kWh of total capacity, though the production models are likely to be specified with either 35kWh, 50kWh or 74kWh capacities – the lattermost with 400km range.

Driving the proto’s wheels is a rev-limited 88kW and 230Nm HyPer 9 electric motor fitted under the bonnet. There’s also a new disc braking system – Jaunt says it is looking at Tesla’s electric brake booster for future applications – and an electric power-assisted steering system that makes this conversion much easier on the arms.

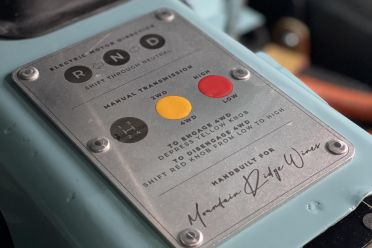

The JLR diffs, axle casings, chassis rails, and parabolic suspension are reworked. Jaunt has also decided to keep the original floor-mounted gear stick, though in operation you don’t need to clutch and change with regularity. It’s more a ploy to keep the driving experience somewhat authentic.

Somewhat hilariously, one of the Defender projects mentioned above will use parts from a Tesla Model S P100, with a 100kWh battery, a Model S drive motor, a single-speed direct drive transmission, and a torsion-biasing rear diff. It’s destined for snowy Thredbo, apparently.

“Building a car like these [referring to the now-registered blue prototype] is as much a product design exercise as anything else,” Budge said.

“What we are trying to achieve with this, there’s no rule book. How do we best solve all these little problems – performance, handling, reliability?

“I think eventually we can sell as many as we can build, both to private buyers for a daily (Budge says he’s had enquiries down this track) and to hotels and wineries. We’re booked to mid 2022, though the more we streamline production the faster we can build.”

When asked about servicing, Budge said the goal was to “formulate a partnership with a service chain”. Battery health checks and things are done by diagnostic tools, whereas the old Landie hardware bits are easier for any mechanic to handle.

“We’re standing on the shoulders of 70 years of Land Rovers needing fixing,” he said.

The other major question, of course, is cost. What are you up for, if you want to buy a converted old Landie EV?

“This is a lot more expensive than an LSA V8 swap,” Budge concedes.

“Scale will help, but right now it’s about $150,000. Half that cost is the restoration and half is the EV build… you can get the parts for an EV conversion for $20,000 if you want, but that’s a very different scenario.”

Where to next? “There’s export potential. We’re already having conversations,” Budge finished.

Ten points for ambition. There’s certainly no shortage of old Landies in farm paddocks the nation over, dying for a new lease of life.