Andrew Maclean

4 Days Ago

Ian Callum sat down with CarExpert over video to talk about his past endeavours, his current projects, and the future of car design.

Contributor

Contributor

Ian Callum has a design resume to die for.

Born in Scotland, the 65 year old has worked with some of the car industry’s most famous brands. In many cases, he’s helped bring them back from the brink.

After a stint with Ford in the UK and Australia, he moved to Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR), where he was involved with everything from the Volvo C70 to the HSV GTS-R.

Most famously, he also led the design of the Aston Martin DB7 and Vanquish.

In 1999, he succeeded Geoff Lawson as design director at Jaguar, a role he served until September 2019.

During his time at Jaguar, Callum turned the brand’s design language on its head, bidding farewell to its retro focus in favour of something aggressively modern.

Having handed the keys to the Jaguar Design Centre to Julian Thomson, he’s now heading up Callum Design.

This is part one of our chat with Callum. Here, we talk about his early days in design, his Australian connection, life working with Tom Walkinshaw, and his early days at Jaguar.

Ian Callum: It’s become quite a well-known career now, but when I was growing up nobody knew what a car designer was unless you were a fan of Pininfarina or Bill Mitchell at GM, or, later on, Giugiario.

It was quite an interesting process. I decided at a very young age, I wanted to design stuff. Even before I went to primary school I was drawing stuff around the house – objects rather than flowers and people.

I realised these things had to be designed at some point, so I thought very early on: I want to be the person who does that.

I was falling in love with cars. I lived in a fairly provincial small town, and there were cars there but not very many exotic ones.

I remember seeing a Porsche 356 drive past. I remember in those days it was brand new, and I thought: “Yeah, that’s where I want to be. I want to be in that world.”

It started there. I was pretty determined from a young age.

It’s weird, going through this [COVID-19] confinement, you tend to think back, reminisce, and think of moments probably a bit more in-depth than perhaps you otherwise would, and I was just reciting these moments to myself and recalling them, and thinking, “My goodness it was only two minutes ago… What happened?”

IC: It’s as clear as crystal, you know. And the day I went to school and gave a drawing to my teacher, and said this is what I want to do when I grow up.

My dilemma now is waking up and thinking, “I’ve done that”.

I’ve done it all, I’ve done everything I wanted to do. It’s quite a bizarre notion, but in a positive way.

But yeah, I started very young, and then I went through the agony of trying to find out how to do what I wanted to do. Of course, in those days if you told your teacher you wanted to be a car designer they just laughed…

Academically I was quite good at school, but this idea of spending my time drawing cars was a bit of a weird thing for someone who was good at maths and doing biology to be doing. Biology is about mechanics and maths is about geometry, which is what car design is about, so it fit quite well.

Eventually I found a way to an industrial design course in Glasgow, and then I went to the Royal College of Art in London with Ford.

We all know Ford. Every car designer I know has been at Ford at some point, and in fact I was at Ford in Australia, in Broadmeadows, for a while. That was my first experience of Australia.

I’ve had quite a lot of experiences of Australia since then, and I fell in love with the place way back in ’85.

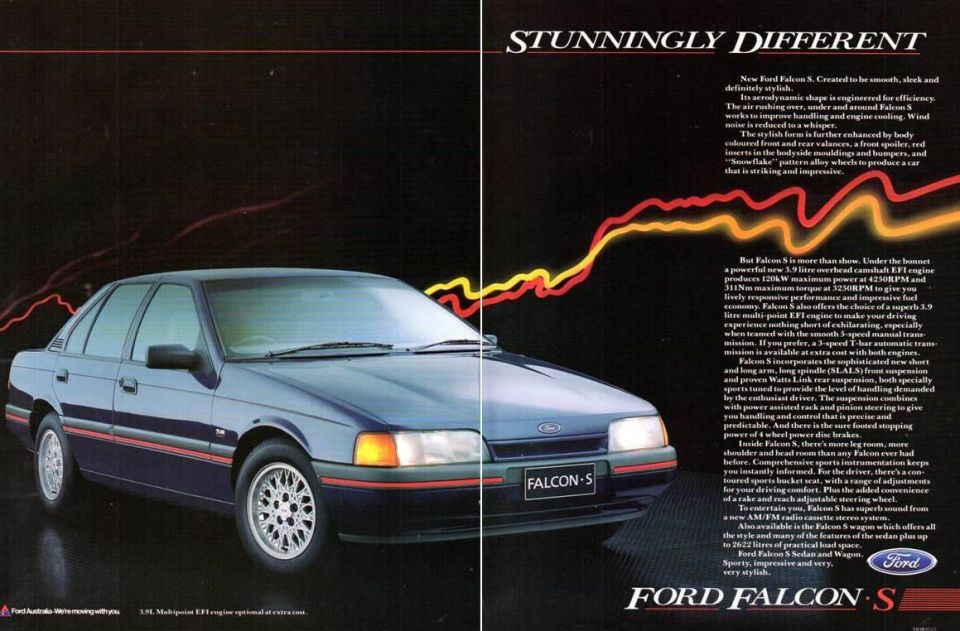

IC: The Ford Falcon EA26, the really good looking one.

I can’t lay much claim to it, I think I worked on the door handles. I did work on the door handles!

That was my place in life in those days, it was quite a good experience. I lived in Melbourne, and my son was born there. He’s an Aussie, though he’s left the country and now lives in New Zealand…

I was at Ford for 10 years, it’s a good training. I think at Ford you really learn the nuts and bolts of real car design, because it’s all about creating something at a certain cost, certain weight, and everything else. It’s quite a strict regime, as you can imagine.

I think a lot of car designers I know – in fact most car designers I know – at some point spend time at Ford. It’s a good training. I’m glad I did that for 10 [or] 11 years.

I didn’t work on anything huge. I worked on the RS Cosworth Escort, it’s probably the most significant thing I worked on.

I travelled a lot – travelled to Italy, Australia, Japan, spent a lot of time in these countries – I tended to always be in the periphery. My dream was to design cars, and that meant the outside as much as the inside.

Most of my time working in England was designing door trims and steering wheels. I think I probably designed more steering wheels than anybody else.

Eventually that frustration got to me and I decided to take a chance and work for TWR. You guys [Australians] know TWR from the good old HSV days. That was Tom [Walkinshaw’s] new business down there in Melbourne.

I used to come down two or three times a year to work on the HSV cars during the ’90s. So all the ’90s cars were mine or my team’s.

It was quite interesting, we’d fly quite a lot. That’s why I’ve been to Australia so many times, probably three times a year at least. I went out for a weekend once, which was a bit gruelling.

I used to design the ideas for the cars on a sketchpad on the airplane going over. John Crennan was the manager then – the boss, the director – used to get so frustrated with me that he didn’t see what I was going to design.

I said, “By the time I arrive it’ll be fine, don’t worry about it”. It always was, but he lived a corporate life and he wanted to see the answers before we started, which I was always reluctant to do. Still am, actually.

I like to work spontaneously.

IC: There’s a book called To Fly a Horse, and it’s all about this notion that creativity comes from moments of inspiration and genius. It doesn’t actually, it comes from hard work…

Like any creativity, inspiration does come, and sometimes I see something and I do feel inspired. And I try and capture that moment of energy to translate that into something that I want to do.

That’s what inspiration is to me, it’s that moment of seeing something that pushes me forward to do better.

It might be architecture, it might be a painting. What I see is somebody’s actually created something I can enjoy, and that pushes me to go and do the same. But that moment of coming up with the ideas is hard work.

You’ve got to work at it, and it’s an incredibly difficult amount of mental energy you need to put into it, but it gets there in the end.

IC: Completely different. Tom – I don’t know if you ever knew Tom Walkinshaw – he was a very clever man.

He knew what he wanted and he gave direction quite specifically if you can imagine, but he also left the door open for you to be who you want to be. I always said to people Tom asked 110 per cent of you without pushing hard, because you felt a loyalty towards what he wants to do.

There was a vision there which was quite clear, and corporate visions tend to be a bit muffled at times with various opinions and perhaps some egos – whereas when you’re working for someone like Tom you know what his vision is, you translate it into your vision, and then it works very well.

It was just 10 fantastic years I had there. He gave me the freedom to do what I felt was right, but kind of under his rules – but that’s fine.

He relied on us a lot. It was very good. Very good.

IC: You don’t realise highlights until after they’re passed, but I suppose the biggest highlight was probably the DB7.

It was one of the first projects I worked on when I arrived. That was because Tom and Walter Hayes, who was actually director of Aston, came up with this idea of producing an affordable Aston Martin, and bringing the company back into profitability – which they did.

I have to admit, I was hugely lucky to fall upon that project as one of my first projects after arriving at TWR.

It was amazing, really, and it was the first time I’d ever been let loose on a car actually. I don’t think a lot of people realised this – I’d worked on cars with teams of other people, including my brother at Ghia in Italy – but I’d never been let loose on a car entirely by myself.

And that’s a hugely difficult process, because you’ve got nobody to rebound from. You’ve got nobody to ask opinions or indeed give some feedback of any kind, except for the modelling guys I worked with, who were fairly ruthless.

On the whole, it was a lesson of self discipline which I think has taken me a long way. You had to learn how to be self critical of your work and that’s what that period did for me, especially on DB7. But my goodness, that was a long time ago.

And then of course there [were] other Astons. I did some work for Volvo – I did some work for Ford, ironically. In fact I did more cars for Ford while I was at TWR than I did when I was at Ford, which was quite funny really.

The power of consultancy!

IC: They didn’t, actually. They were still separate at that point, it wasn’t until later on.

I was at TWR when Volvo was bought. Jaguar was certainly owned then, and Aston was bought. There was a coming together of family at that point.

While I was worked at Volvo they were very much independent. When Ford bought them the cars I’d worked on were out on the road. The C70 was the one I worked on the most.

IC: I think they’re very honest. They were a British sports car as opposed to Italian or German, and I think that had a certain caricature.

I’m not sure that caricature prevails these days amongst car brands, but certainly in those days that sense of restraint…

The DB5 and the DB4 – although they were designed in Italy, of course – but they picked up on this really restrained maturity that Astons had.

They were seen as a gentleman’s car, and that had a certain charm. It fitted into the British culture which other people – non-Brits – found quite fascinating. Not always to the best advantage, but there’s always this intrigue of British culture being the epitome within an Aston.

There’s always something else as well that I think is quite intriguing with car companies, it’s the name. If you think of the name Jaguar, for instance, it’s just a beautiful name and it rolls off the tongue. If Jaguar had been called something else I don’t think it would’ve succeeded the way it did…

Aston Martin as well, it just sounds so exotic doesn’t it? Aston Martin. It’s very down to earth and reasonably cold, Aston Martin, but it’s just a lovely name to spell out – like Ferrari is a lovely name to spell out. Maserati. They have a ring to them, and I think certain names have that – that’s part of it I think.

IC: When you look into the history of Aston Martin it was a bona-fide race car. Their history was all about performance, it became more the gentleman’s GT car in the ’50s and ’60s…

They were built for hillclimbs at Aston Clinton – where the name comes from – by Mr Martin. They were named after hillclimb and one of the owners of the company, that’s where it came from.

IC: I arrived when the XJ was about to go through its final stages of development. The XJ I’m talking about is the last traditional XJ – the 300, I think it was called. It was the aluminium one, which was the first all-aluminium car of its type.

In that respect it was a very modern, very up-to-date car. Unfortunately its style and design kept emulating the past.

This what I saw as the problem… Once [Jaguar founder, Sir William] Lyons left the business in the early/mid ’70s effectively, there was nobody really pushing the brand forward. They just kept copying the past, and that was the mistake they made.

Lyons would never have done that. He wasn’t sentimental, Lyons, he kept pushing forward.

That is what I think happened to Jaguar, it became a sentimental car company. It took the customers with it for that reason. Of course, eventually, they all got very old.

So I saw an opportunity after that car to recreate the brand back to where I felt it should be, and back into the glamour and modernity of where the cars used to be back in the early/mid ’60s or late ’60s.

That was my reference to Jaguar, and that’s what I tried hard bring back to it – I thought it was a rightful thing to do.

Of course it took quite a lot of persuasion, because there were quite a few diehard Jaguar fans within the business who felt it was about tradition, and that’s what they felt most comfortable with.

We had a lot of American management at that point because Ford had come into play, and they certainly had a view that Jaguar – jag-war – was a good old English car company, it should be traditional. I didn’t agree with that.

It was an uphill battle. I’m not decrying the style of the cars, they were beautiful. I see that aluminium XJ now and it’s a lovely car. If you see one that’s been slammed and tricked up a bit it looks good, but it just wasn’t where the company should be, so I pushed forward.

Where I rest my case is; if you look at the XJ – it’s now out of production, it’s 10 years old now – and stack it up against the other cars of that era it still holds it own, as a Jaguar should do. It’s still individual, but it’s modern at the same time.

It was a very different place. My objective was to turn it into somewhere that was relevant to the 21st century, really – exactly when I started, 1999. I thought this is it, I’ll call it a 21st century car company.

IC: Never. Never. I never had one doubt about it.

The only trepidation I had was towards the politics I had to face, of it going through that. But once we got past XF, we were well past it.

Because we did the XK first, which really was an evolutionary car. It’s still, I think, quite a modern looking car, but the car it replaced was a very beautiful car. I think the XK did the job well, but the XF changed it. Once we got past that was really very little pushback.

And when we got to XJ, we had a new boss in Geoff Polites, another Aussie. He was our director, and sadly he’s no longer with us – remarkable bloke. When we were doing the XJ, I decided after XF to really push the boundaries again.

Let’s not just rest on this, just keep pushing it. Start taking a few chances, which we did. And they were controversial, especially around the tail lamps and such, but I still hold my opinion in them. I think they’re fine.

Geoff was CEO of Jaguar Land Rover at the time, and he just kept everybody out of view. He said leave Ian alone. He was great, he was a man of vision.

Geoff Polites is quite well known in Australia. He was a car dealer I think, so he knew customers. He was a great boss, but sadly he died young.

Once we’d gone into the ownership of Tata – had he lived, he should have been there then. I think that would have been quite an interesting time for him, but sadly not to be…

He was a man of the people, a man of understanding cars. Most Aussie people that are involved in cars really love cars, that was I loved about the culture there. It’s a bit like the California culture, people love cars.

IC: Absolutely, it was a breath of fresh air. I would have won through in the end, but he allowed my energy to be put into the design rather than pushing back the waves of resistance. That was a big plus that he gave me.

It was a good time. The XJ evolved.

Really, after that, I didn’t feel the same freedom at Jaguar that I’d felt. There were always questions, “Is this the right way to go?’.

People there at the upper levels, they didn’t resist what we were doing. They just wanted to be convinced all the time that, perhaps. “Is the right way to go or not? Can we trust you?”.

It was a valid enough question, we all get it wrong sometimes. But with Geoff it was a case of trust, I think that was the big thing.

After that I think we got a little bit more conservative again, the marketing guys got confident and said, “We need to be a little bit more proactive on the packaging side and create something that’s a bit more useful’.

Well, Jags are not designed to be useful, they’re designed to be desired. It was always a bit of a point of tension to say the least.

The F-Type wasn’t so bad because an F-Type wasn’t designed to be useful, it was designed to be driven and to look at… although the packaging was hugely demanding. On the sedans, the saloon cars, it was always a bit tricky.

The second XF ended up a little bit more conservative than the first because they felt more headroom would be a bit more in keeping with the 5 Series and the E-Class. As much as I tried to resist it I got waylaid [laughs].

IC: Well you do the best you can. Design is about taking on board all the aspects you have to and dealing with them, that’s what design is.

I say this to students and people breaking into the business: You’ve got to deal with what you’ve got to deal with, you can’t just create wonderful shapes and expect someone’s going to build it or make it. There’ll be something that says you cannot do it.

It might be as simple as cost or manufacturing ability, or legislation, or weight. Design is problem solving, and part of that is a problem-solving aesthetic within the boundaries.

In motor cars nowadays you have more and more forces coming at you to create this object, whether it be aerodynamics, cost, the size of people.

When I designed the DB7 people were smaller. Twenty, 30 years later people are now bigger, both in breadth and height, so you have to accomodate these things.

IC: People were smaller! When I was growing up I was average height, I’m five-foot-eight.

I look around now and I’m below average height – some of it’s just because I’m getting old – but five-foot-eight when I was growing up, I was average height.

I built the DB7 to fit me. I fit perfectly [laughs].

IC: It’s pretty self indulgent, isn’t it? It was Harley Earl who said, ‘If it looks good enough you’ll crawl into it”.

Tune in tomorrow for part two of our chat with Ian Callum, where we talk about the I-Pace, his affinity for Jaguar, his new project, and the challenges facing the automotive industry.

Scott Collie is an automotive journalist based in Melbourne, Australia. Scott studied journalism at RMIT University and, after a lifelong obsession with everything automotive, started covering the car industry shortly afterwards. He has a passion for travel, and is an avid Melbourne Demons supporter.

Andrew Maclean

4 Days Ago

Max Davies

4 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

3 Days Ago

Max Davies

1 Day Ago

Josh Nevett

9 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

5 Hours Ago