Josh Nevett

5 Days Ago

ANCAP is Australia and New Zealand’s independent vehicle safety authority. How does its testing compare with that of US safety authorities the IIHS and NHTSA?

Contributor

Contributor

Fundamentally, a car is a metal cage that carries its passengers at a very high speed down a road. This means that the safety of this cage is critical in the event of a crash.

For this reason, vehicle safety is a key consideration in the new car purchasing process.

In the past, vehicle safety almost exclusively referred to how well the vehicle protected its occupants in the event of a physical crash with another vehicle or object.

Today that definition of safety has expanded to also include preventative safety, such as the availability and effectiveness of active safety equipment.

Testing remains the main way to judge a car’s crashworthiness and preventative safety systems.

For the Australian and New Zealand markets, this testing is undertaken by ANCAP (the Australasian New Car Assessment Program). Its European counterpart is Euro NCAP, with which it has harmonised its testing protocol.

For brevity, we’ll refer only to ANCAP in this article, however understand Euro NCAP employs the same tests.

For the US market, the two primary organisations that crash test vehicles are the NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) and the IIHS (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety).

The NHTSA is a US Government agency, while the IIHS is a nonprofit funded by insurance companies.

While ANCAP and the US safety authorities have the same overall goal – to test vehicles’ safety and inform consumers which cars are safest – they use different testing standards that continue to evolve.

A model that appears the same on paper can be built to different specifications for different markets, and this means that models that have the same design and name overseas may not have the same safety performance as their Australian and New Zealand equivalent.

As there are different specifications and different testing protocols between safety authorities, you won’t see, for example, Hyundai advertise its US safety ratings for the Palisade, even though it hasn’t been tested by ANCAP.

MORE: ANCAP ratings: everything you need to know MORE: It’s time for smarter ANCAP ratings MORE: Australia’s best-selling cars without ANCAP ratings

When discussing crashworthiness, arguably the first type of crash that comes to mind is the car crashing into an object or another vehicle, and all three agencies perform frontal crash tests.

ANCAP conducts two types of frontal crash tests. The first is the full-width frontal test that aims to simulate a head-on collision, and slams the front of the car (its full width) into a rigid wall at 50 km/h.

Additionally, ANCAP also undertakes a frontal offset test. Rather than the full width of the vehicle, 50 per cent of its width on the driver’s side makes contact with a 1400 kg trolley that uses a deformable aluminium face.

In this testing scenario, both the car and trolley travel towards each other at 50 km/h to simulate a head-on accident with an oncoming vehicle. This replicates real world scenarios such as a fatigued or inebriated driver veering across the centre lines into an oncoming lane.

The NHTSA performs a frontal crash test similar to the ANCAP full-width frontal test, but at 35 mph (56 km/h).

In contrast, the IIHS doesn’t undertake a full-width frontal test. Instead it undertakes a ‘moderate overlap’ test. Somewhat similar to ANCAP’s frontal offset test, 50 per cent of the car’s width on the driver’s side hits a stationary deformable aluminium barrier at 40 mph (64 km/h).

IIHS also performs a ‘small overlap’ frontal test on both driver and passenger sides that is designed to simulate the front of the car encountering a tree, power pole or similar. In these small overlap tests, 25 per cent of the width of the car hits a rigid barrier at 40 mph (64 km/h).

T-bone accidents, where an oncoming car strikes the side of another car, are perhaps some of the most dangerous types of accidents to be involved in.

All three agencies recognise the potentially devastating impact of these collisions and have developed a test to evaluate a car’s safety in the event of a side impact.

The IIHS has revised its testing procedure for 2021, and now uses a trolley with a 1900kg honeycomb barrier travelling at 37 mph (60 km/h) that strikes the side of the car.

In contrast, ANCAP uses a barrier that travels at the same speed but is lighter at 1400kg. Meanwhile, the NHTSA utilises a slightly lighter barrier than ANCAP (at 3015 pounds or 1368kg) but at a slightly higher speed of 62 km/h.

MORE: Tough new US side impact crash tests expose SUV safety flaws

In addition to simulating T-bone crashes, ANCAP and the NHTSA also perform an oblique pole test to replicate a run-off road event, where the side of a car might hit a tree or pole.

Both the ANCAP and NHTSA versions of this test (the NHTSA version is known as the side pole test) has the car colliding at 32 km/h into a fixed, rigid pole aligned to the driver’s seating position at an angle of 75 degrees.

ANCAP exclusively repeats its side impact and oblique pole test to also determine the ‘far-side impact’ of these collisions.

These far-side tests aim to determine whether passengers on the opposite side of the car are hurt during side impacts, by coming into contact with their fellow passengers or part of the vehicle.

They are a reason why several manufacturers are now introducing centre airbags to ensure good performance in these tests.

Rear-end collisions remain an occurrence on our roads, and one of the adverse effects of such collisions are whiplash injuries, or where a severe jerking motion can cause serious neck and head injuries.

To test whiplash risk, ANCAP takes a seat from the test car and mounts it on a sled, that’s moved forward at a moderate and high average acceleration of 4.9g and 6.4g. The IIHS conducts similar whiplash tests with an average acceleration of 5g.

Cars aren’t the only users of the road, and potential accidents can also involve pedestrians.

To this extent, ANCAP exclusively undertakes pedestrian impact tests, that assess the risk of injury to a pedestrian’s head and legs at 40 km/h on various locations of the front of the car, including areas of the bumper, bonnet and windscreen.

Rollovers are another way that vehicle passengers may be injured, and both the IIHS and NHTSA test this in different ways.

The IIHS makes use of a roof crush test, whereby a machine pushes an angled metal plate down on one side of the roof. The peak force applied by the machine before the roof is crushed by 5 inches (13 cm) is determined, and compared to the vehicle’s weight to determine the roof strength-to-weight ratio.

IIHS considers a ratio of 4, whereby a roof is able to withstand a force of at least 4 times the vehicle weight, to be necessary to achieve a ‘good’ rating.

In comparison, the NHTSA uses a more predictive test that makes use of a sharp cornering manoeuvre to determine how top heavy a vehicle is.

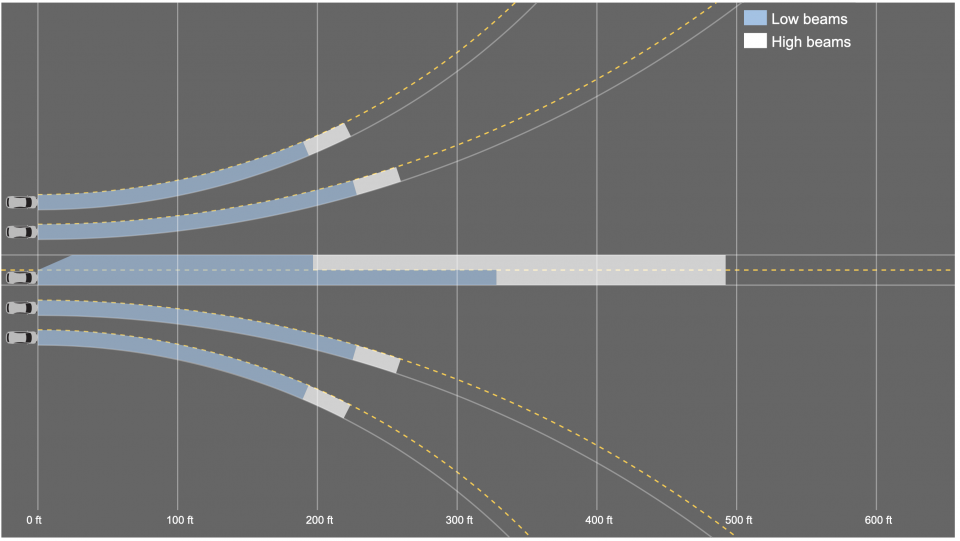

Headlights are key to driving safely at night, and the IIHS is the only agency mentioned here that rigorously evaluates headlight performance.

Both low and high-beams are tested on curved and straight roads, and the tests aim to determine how far the light reaches with an intensity of at least five lux.

ANCAP is the agency here with the most comprehensive testing of active safety systems.

The agency evaluates not only performance of autonomous emergency braking (AEB) systems in relation to cars, cyclists and pedestrians, but lane support systems (such as lane-departure warning and lane-keep assist), and other systems such as driver fatigue and speed assistance.

The IIHS tests AEB performance in relation to other cars and pedestrians only, and doesn’t test the performance of other active safety systems such as lane support.

For car-to-car AEB systems, the IIHS evaluates performance at test vehicle speeds of 12 and 25 mph (20 and 40 km/h) compared to the 10-50 km/h range tested by ANCAP.

The NHTSA may not directly test AEB performance, but has encouraged carmakers to introduce the feature.

Josh Nevett

5 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

4 Days Ago

Angus MacKenzie

3 Days Ago

Matt Campbell

2 Days Ago

James Wong

18 Hours Ago

Marton Pettendy

18 Hours Ago