Andrew Maclean

5 Days Ago

Contributor

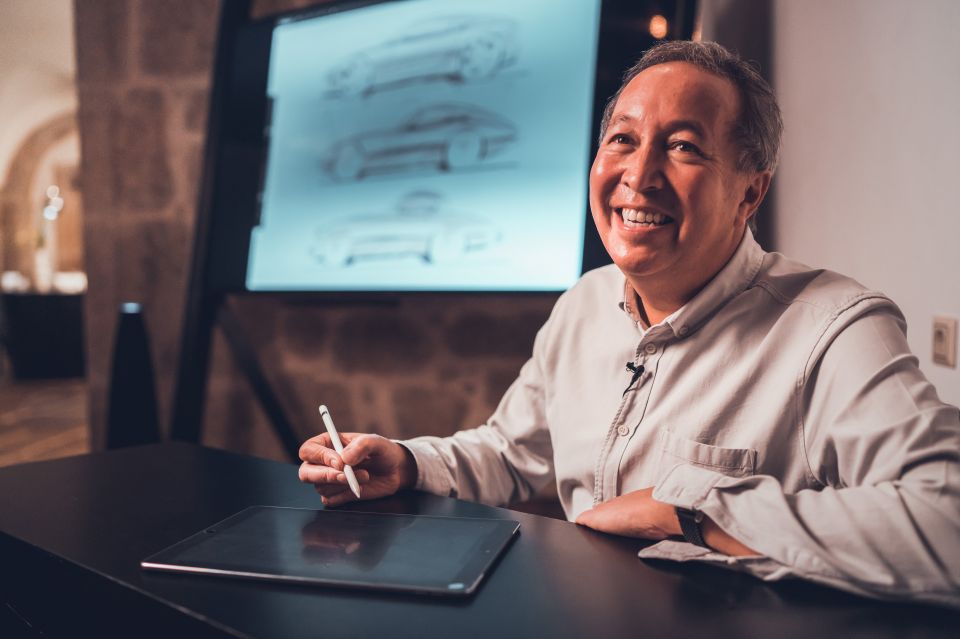

Julian Thomson has a dream job for anyone who grew up sketching cars on their schoolbooks.

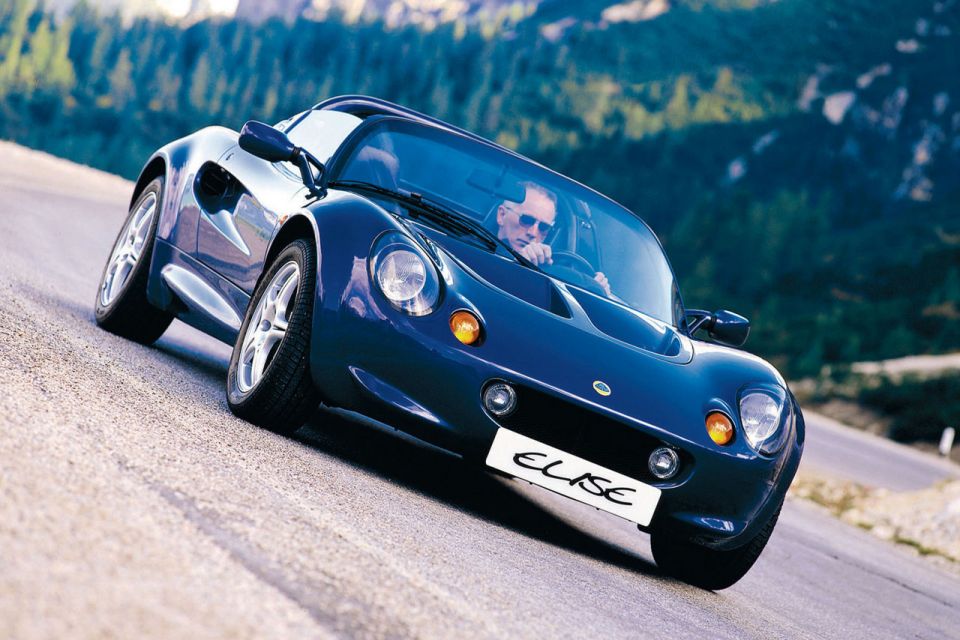

The affable Brit led the design of the original Lotus Elise in 1996, before a brief stint at the Volkswagen Group.

In 2000 he landed at Jaguar – at the time under Ford ownership – and, alongside Ian Callum, set about reforming the brand’s design language.

Late last year, he took over the role of Jaguar design director from Callum.

Speaking to CarExpert on a video call from hybrid home office and attic, Thomson spoke about his life before Jaguar, the process of dragging its design into the 21st century, and how he plans to move the game on again.

Julian Thomson: It goes back a while now. I was one of those kids who kept on drawing cars as a kid, just always drew and always drew – and my schoolwork suffered a great deal as a result.

I did pretty badly at school, but luckily someone who was actually a designer, an ex-designer at Rolls-Royce, saw some of my drawings and put me in touch with the Royal College of Art in London, and that’s when I had a bit of focus to go after it.

Eventually I got there as a postgraduate. I was sponsored by Ford, and when I went as an intern to start at Ford in the UK I met Ian Callum.

He was the first real designer I met as a student, and we remained friends ever since – and we still are today.

I worked for Ford for a couple of years, found that quite stifling and too corporate, so I went to work at Lotus – and I was there for 11 years, and that’s where we did the Elise.

Then I had a couple of years at Volkswagen in the concept design studio in Spain, and since 2000 I’ve been at Jaguar, where I’ve been advanced design director until last year, and now I’m design director.

So that’s a potted sort of history of me moving around a bit.

JT: It was a strange company… If you look at the record between myself and Ian Callum, you know, as we were friends we were both doing the same thing.

He was resurrecting Aston Martin through his work at TWR, and I was doing the same at Lotus.

We came together with a much bigger challenge of doing Jaguar. I think we both fancied the brand, and the opportunity to take what was a British company in a very similar state to where Aston and Lotus had been.

It had just got a little bit stuck, and a bit freaked out by the huge level of competition from abroad.

In both cases they went back to their roots, if you like, and that’s what Jaguar did as well, really wanted to go back to their roots. A lot of big brands, they get stuck in a rut.

Car brands or fashion brands, anything. They’re victims of their own success, and they don’t always know how to best modernise their history and heritage, and how to be relevant going forward.

JT: If you take Jaguar when we joined in 2000, it had… if you actually looked at the customers, it had one of the best loyalty rates of any brand.

People just loved their cars so much. Problem was, it wasn’t attracting new customers into the brand, and the people who had them were holding onto their old cars.

It’s a problem you see a lot in these very traditional luxury brands, it’s a problem which Lincoln and Cadillac encountered as well. They just don’t change with the times, and they’ve sort of grown older with their customers.

So in the late ’90s with vehicles like the XJ, they’d been essentially the same car for, you know, 20 years. They’d go out to customers too much and ask them what they liked about the vehicles, and the vehicles would stay in the same place.

That was very disappointing really. If you look at the history of it, Jaguar has really got a tacit reputation as an innovative brand, that what its whole legacy is built on – vehicles like the E-Type and the D-Type, and the original XJ6.

Just engineering-wise and design-wise, extremely innovative. And also, sort of breaking the mould in terms of where these vehicles are placed and priced, and what they did to the market.

Over the last few years, our job has been to make the brand more contemporary, and try to get back that spirit, that inspiration, innovation back into the brand.

JT: I think, for myself and Ian, we hadn’t been used to doing so many cars all in one go, you know, and we were really given the keys to the toy shop. We were allowed to just… we did so many cars, just one after the other, bang bang bang.

It was really exciting. So many vehicles going on, such a busy studio, and it continues to be so as well.

We’ve got that energy back, we’ve got that momentum back, and it’s very exciting.

JT: Umm, no. I think with a designer, you always are… all designers want to be car designers, and love being car designers. It’s not something they’re reluctant to do, and they all – I won’t say we’ve got big egos, but they’ve got a tremendous sense of belief.

They really do believe what they’re doing is right, otherwise they wouldn’t be doing it. They have very, very strong opinions.

We don’t sit around going ‘are you sure, should we do this… I don’t know about that’. We all wholeheartedly believe as a team that it’s the right thing to do.

Any designer, any car designer feels he’s held back by the industry. He’s either held back by his management, held back by marketing, held back by cost. He always wants to go the extra mile, he always feels he can go further.

There’s never a question of us being timid in this, we’re just like dogs pulling on a lead.

JT: I think what we’ve done over the last few years… We’ve gone from a pretty small manufacturer with only a couple of vehicles when we joined, up to a large volume producer.

We’re one of the fastest-growing luxury brands of the last few years, and we’ve added SUVs, and we’ve added more saloon cars. We’ve had a period of great expansion.

Really, what we’ve been trying to do is establish ourselves as a very credible, contemporary, premium brand. We’ve gone into all those very competitive market segments with all our vehicles. We’re there now.

I think going forward, if I was to make any changes, I’d perhaps like to make our cars more individual – really turn up the wick on elements of Jaguar character, be it the beauty, the luxurious interiors, the sense of specialness.

I think we’ve grown into these segments but now we really want to establish them, and really make them own. Really offer something which is very, very different. When you get to a big car company and you’re playing in competitive segments, you’re always playing off the rational with the irrational, and finding the right position between those two.

As you become more rational you become more normal, and I think we just need to be more extraordinary in everything we do – be more creative, more different. I think that’s what people associate with our brand.

JT: We all have to play by the same rules. We’re well aware of them.

You could design a car in the old days with, I guess, about five or 10 people. Now we have 10,000 engineers at our beck and call.

They’re pretty good on that sort of stuff. What would have been a team of people designing a car before, now those people are just doing pedestrian impact, the same sort of size team.

We need to really make sure that we communicate with those people. We have an advanced research department associated with the local university where we do a lot of the technology research, and we feed our design requirements into there – which are mainly led from the aesthetic – to really make sure we get what we want going forward.

At the same time, my design team, I have an internal design engineering department of about 40 people just to support design initiative, to go and be the diplomats, and go out into the wider organisation to try and broker deals and bring technology forward.

JT: I get asked a lot whether electric cars should look different, and some markets say electric cars shouldn’t have a face on them, they should have a grille on them that’s all plastered over or body-coloured, or this and that.

Then we talk about the proportions of these vehicles being different, but at the same time we do this with a backdrop of what is the most beautiful aesthetic to have for a car.

There’s a most beautiful aesthetic you have for a house, or a person indeed. There are certain qualities of proportion, of balance, of purity which always win out.

We try to do that. A Jaguar should always be honest to its engineering which lies underneath the car. So we don’t want to torture a shape over a set of engineering criteria which is completely at odds with it.

It’s very important we work very closely with the engineers to the package and the base, the hardware under the car to suit the proportion we want.

I think there’s a couple of issues here. There’s electric cars, should they look different? I would advocate just doing the best looking car, I wouldn’t try to necessarily make it look electric or not electric.

In terms of identity, the market is full of vehicles. It’s absolutely bursting with new vehicles. Against this we’ve got lots of Chinese brands growing in credibility, we’ve got lots of American startups coming on stream.

So to actually stand out in the market is getting increasingly difficult. What we think is, people approaching a brand like Jaguar want the car to look like a Jaguar. They want to buy into that club, they want to show they’re knowledgable about cars, appreciate our legacy and our history.

We have to make them more Jaguar-like, not only in how they look but how they behave, and how they’re differentiated in the market. We need to really make sure we build our identity more strongly going forward.

JT: The F-Type is obviously based on a previous car, so it was bringing it into line, into our philosophy.

I think the new XJ when it comes out – which we’ve made no secret of, it’s in development, you’ve seen spy shots of it – that one is probably going to be a bigger beacon for our future design.

That car in terms of… the identity of it, the way the body surfaces are. That’s going to be our latest, newest car, and that is a car I’m very excited about, because it’s more Jaguar than ever before.

It really does put a stamp on what we’re trying to do in terms of our future direction.

JT: It is! It’s also intimidating.

It’s a task we really, really relish and we’re very excited about. We can’t wait to show these cars off, and get them out the door.

It’s a brilliant opportunity, and to be custodian of the Jaguar design philosophy and be responsible for that is a tremendous task, and a tremendous honour. I’m only the third Jaguar design director ever, and the company is going to be 80 years old soon, so it’s a fantastic honour.

JT: [The old Jaguar Design Studio] was a pretty… it was actually one of the oldest design studios in the world, in terms of clay studios. And it was used by Chrysler, and Peugeot, and all sorts of manufacturers like that.

Once you set down a template for a design studio, which had these modelling plates and all these machines, they tend to get inherited by other car companies, because they’re difficult facilities.

But it was very, very old. The roof was leaking, the floors were all cracked. It was very, very cracked. It was really designed to do one car a year, we were doing three or four. It was far too small.

We moved to a new, state-of-the-art facility a year ago more or less – in August, actually – which is actually fabulous, one of the best studios in the world.

What the old studio did have was a tremendous sense of family. In face of adversity, and leaking roofs and buckets on the floor, we did all come together. The new facility is humungous, it’s very, very impressive, but I was very, very anxious that the team has that same sense of family, and the same sense of communication and helping each other.

Design is a very collaborative business, and it’s very important for us everyone feels very freely to walk around and talk to people, and chat about what they’re doing – sound off things against each other. So the whole studio was designed very much with communication in mind.

It’s an extremely open-plan area with lots of glass, where from several vantage points you can look across and see your colleagues, and see they’re there – walk to their desks, walk to them.

It’s based very much around the modelling plates. We’re still a great believer in a lot of clay models, and a lot of investigation into clay models, so the clay facility is one of the best in the world, and it’s working out very well for us.

When we were forced to leave last month, it was very sad for us to leave the facility because there’s a great deal of energy and spirit in the place, a great buzz. So we look forward to returning there as soon as we can.

JT: Well, we’re doing this a lot. We’re on [Microsoft] Teams a lot.

We’re managing okay, actually. We miss the clay models. If you picture the scene of a design studio, I spend most of my day walking around.

Looking at clay models, and then walking up to people drawing, looking at screens, having a bit of a gossip, comparing notes from one design to the other, going off to the models putting some modelling tapes on…

I usually spend very little time on a computer. Anyone who sends me an email, it’s unlikely to be answered for a very long time.

We’ve had to adapt and I think the good thing is, we’ve all been forced to press the pause button and step back.

We’ve got a crisis which is very frightening, and everyone is forced to reevaluate their own lives and what’s important to them – and also reevaluate their work, and what they’re designing and why they’re designing it, and what they want to say.

Sometime we’re still caught up in such a sausage machine of production that we don’t always have enough time to step back from what we’re doing and examine why we’re doing it, what makes us different, and what our designs… a greater purpose if you like.

So it’s been very good for that. We’ve been communicating a lot on Teams, we have lots of digital reviews. We’ve managed to take all our high-powered computers home and people are still working on them, so we can still do all the computer modelling, and all the computer animation we want.

We’re adapting pretty well. Even with our Chinese studio we’re doing virtual reviews, just walking around with cameras and things like that. We can do these things.

As we get going a bit I can review clay models by driving into our private viewing area and just literally driving around the clay model in my own car and on the phone I can feed back to people in the design team about what I think about something – without going anywhere near them, even getting out of the car.

I can do a sort of drive-by design review.

JT: There’s a lot more resource online to find out about these things, but obviously a lot more resource online is a lot more competition [laughs].

At the same time there’s a lot more car design jobs as well.

What I look for in a designer is someone who’s got a questioning mind, an analytical mind. It’s quite a cruel thing to say, but when I receive a designer’s portfolio I can tell within about three or four pages whether that guy is right for us.

And I think what we’re looking for is a person who can – with a clean sheet of paper, not referencing other vehicles – come up with some ideas for his own vehicles, his own cars and what he thinks it should be.

But more importantly, what we’re looking for is this process to build on your ideas, to refine your ideas, to pick out the good for the bad and have this process of gently honing something and getting it better.

I would say to those people, just draw, and draw, and draw, and keep drawing, and keep inventing. Just, like me, just keep drawing stuff. Don’t stop, and just keep questioning things.

It’s not a matter of just drawing, it’s being able to just question things, progress things, come up with new ideas and see them through. That’s what we’re looking for.

JT: I saw on your bio that you’re a big classic BMW fan, which doesn’t go well with us.

JT: I do have a share in an E28 BMW with my son, E28 5 Series. But that’s only a half share, he’s a keen BMW fan.

I have two SVR Jaguars, I have an F-Pace SVR and an F-Type SVR. Those are our sort of daily drivers, which are a bit over the top, but we’re very lucky to have those.

I bought a Ferrari Dino in 1984 which I still have, and then – I try to encourage all my designers to ultimately buy cars they’ve designed, good or bad.

I have a Lotus Elise Sport 160… when I was at Lotus we used to do a lot of work for Honda in Offenbach, in the Frankfurt studio, we did the winning clay model for the Honda EP3 so I have a Civic Type R from that generation which I’ve Quaife differentialed, and special brakes and engine tuning – you know, done the lot. This is like a track car.

I love little hot hatchbacks and things, so I have a Renault Clio Trophy 182…

JT: Everyone says that’s the best analogue hot hatch, I have one of those.

I’m a big fan of Colin McRae and rallying, so I have a Subaru Impreza RB5. I’ve actually got another Impreza in Thailand as well, at my parents house in Thailand.

What else… My girlfriend’s got a Porsche GT3, and I think that’s all.

I’m lucky to have all of those. They’re all running, they’re all working, the Ferrari’s actually being painted at the moment but they’re all up and running.

I’m actually using those classic cars to do my daily errands, buy eggs and things, to make sure they all keep going.

JT: Yeah, it’s a nice opportunity.

JT: Ahh, I don’t know. We’ll have to see… I haven’t been out in the Lotus for a bit, so maybe that’ll be the one. We’ll see.

I don’t have a favourite to be honest!

Take advantage of Australia's BIGGEST new car website to find a great deal on a Jaguar E-Pace.

Scott Collie is an automotive journalist based in Melbourne, Australia. Scott studied journalism at RMIT University and, after a lifelong obsession with everything automotive, started covering the car industry shortly afterwards. He has a passion for travel, and is an avid Melbourne Demons supporter.

Andrew Maclean

5 Days Ago

James Wong

5 Days Ago

Damion Smy

3 Days Ago

Paul Maric

3 Days Ago

Max Davies

2 Days Ago

Gavin Womersley

1 Day Ago