Max Davies

2026 GWM Haval Jolion review

1 Minute Ago

Giving people a rebate for trading in their less safe and higher-emitting old car for something new, has numerous upsides for any government fumbling for economic and environmental levers.

Senior Contributor

Senior Contributor

The governments of Australia are scratching their collective heads seeking ways to stimulate the economy as we (hopefully) move past the harshest COVID-19 restrictions.

While being aware there’s only so much taxpayer money to throw at ideas in enthusiastic Keynesian fashion, there is one program I’ll advocate dusting off beyond the well-received instant asset write-off extension.

It’s an oft-discussed and well-known scheme incentivising people to get rid of their old car and into a new one, colloquially known as ‘cash for clunkers’. Subsiding new vehicle purchases, contingent on trading in an old car, pulls forward discretionary spending and improves the state of the car parc at once.

And it’s not just merely one I’m promoting out of self-interest.

The car industry is an economic driver, so cultivating sales of new models does correlate with bolstering economic indicators. I’m talking to you, politicians. The Australian Bureau of Statistics says just that, adding that such data is used “for analytical purposes by government policy areas and economic analysts”.

Consider the fact that new car dealers employ 56,000 Australians and pump $13 billion into the economy, according to the AADA lobby group. And consider further the economic force of the 60-plus car manufacturers and their thousands of workers who benefit directly from sales.

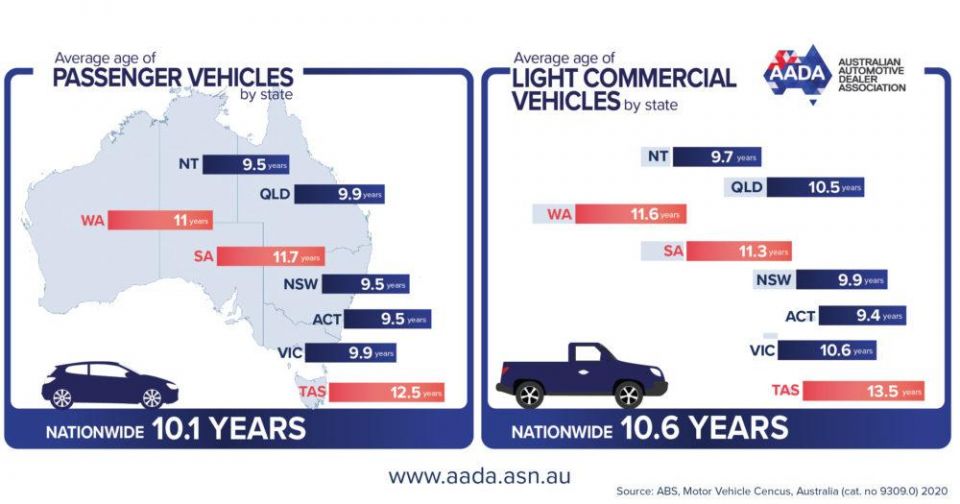

Why is cash for clunkers a goer? Australia has an old car fleet. The average age according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics is just over 10 years. This compares to around 8.6 years in Japan, 6.9 years in Germany, 8.1 years in the UK, and a rather elderly 11.8 years in the USA.

So even though more than one million new vehicles find homes every year, it’s simply doesn’t whittle down the fleet average.

There’s zero doubt that new vehicles offer benefits not just to their owners, but society as a whole. That might seem portentous, but it happens to be true.

For one, they’re much safer, as this 2017 ANCAP crash test between old and new Toyota Corollas shows. ANCAP also found that the rate of fatal crashes is four times higher for older vehicles (pre-2000) than for new vehicles

New cars designed to meet the latest crash safety standards crumple on impact but leave the passenger cell more intact, and they feature systems such as stability control, side airbags, autonomous emergency braking, and active bonnets.

Put simply, you’re better off crashing a new Kia Picanto than an old Barina.

They’re usually a bit greener too, despite Australia’s predilection for thirsty utes and big SUVs. Modern engines use less fuel than they did a decade ago, because most regions around the globe require companies to reduce their CO2 emissions.

So we see more cars toting small-displacement turbocharged engines, idle-stop shut-off systems, regenerative braking, particulate filters, coasting modes that decouple the engine down hills, eco modes that numb throttle take-up, petrol-electric hybrid drivetrains (about half of all 2020 Toyota Corollas and RAV4s for instance), and low-rolling resistance tyres.

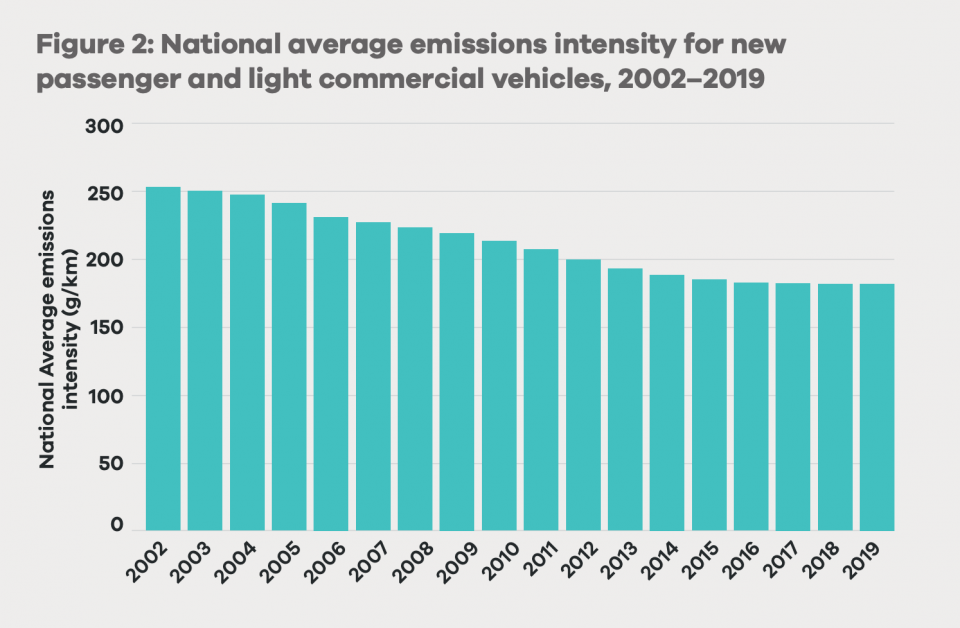

The data is clear that each year, the average new vehicles being purchased are greener than those that preceded them, as this National Transport Commission report finds.

Yes, Australia’s emissions cuts were nowhere near as sharp over the term as what Europe’s were, with a new-fleet average north of 180g/km last year compared to about 120g/km in Europe, yet the improvement against cars bought in 2002 or 2009 is clear. That’s the real lesson for mine.

It all follows then that new cars are economy-drivers, inarguably safer to their occupants and the general public around them, and better for the environment. Which is why this program isn’t just about self-interest, but collective interest. But how do we go about doing it?

Well some of you might remember the last time this issue was seriously put forward, with then-PM Julia Gillard’s ALP government pitching a $2000 subsidy for people to update their old cars. It was labelled a Cleaner Car Rebate and was designed to get old guzzlers off the bitumen.

Of course, back then Australia still had a large local car manufacturing industry to help out, which is a far smaller factor today since remaining local manufacturers work at lower scales.

If you were to do something similar to this today and focus on emissions cuts as the key driver, then you could stipulate the purchase of a hybrid or electric vehicle where appropriate for the user case.

That would slash personal transport emissions. But it would also be ridiculously hard to oversee at the best of times. You could offer a two-tier policy and give those buying a car that emits below 100 grams of CO2 per kilometre a higher subsidy level, but I digress…

A new diesel Ford Ranger is going to emit fewer toxic particles and carbon dioxide than a 2010 model (195g/km CO2 versus 274g/km, excluding NOx) so focusing just on the greenest new cars to the exclusion of others lacks scale and scope, and arguably puts policy above practicality.

The policy would need to be simpler: trade-in a car older than 10 years, for a new one, and you get a rebate of $X. In most cases, the new car will be better for society and its owner, and will stimulate one of Australia’s biggest economic sectors merely by being purchased.

At the same time, it could potentially incentivise those working in the scrappage industry. Without knowing the intricacies of that sector, we’d find scrapyards nationwide flooded with old cars. Yet that’s an opportunity as much as it is a problem.

I’m not going to bother getting comment from any car company executive or lobby group, because of course they want such a scheme. It’s the definition of self-interest, much like Mercedes-Benz stressing about the luxury car tax.

But there’s a heap of evidence around the application of similar schemes undertaken elsewhere to lend context: As you can see here, programs like this have been trialled across the Americas, Europe and Asia. Admittedly to mixed success depending on how many strings are attached, and how laser-focused a given plan is.

There’s evidence that there’s a risk of people overwhelmingly buying cheap new cars – as this US study found when looking at an Obama-era policy – but unlike the USA we don’t have local car brands to cater for.

An imported-car sale is an imported-car sale. And a smaller proportional sales-tax yield is still better than no tax yield, which people keeping their old cars causes.

The other flagged issue is discerning how many people purchased a new car and jumped out of an old one, that wouldn’t have done so irrespective of the subsidy. Would we just end up paying people to do what they already planned to do regardless?

Clearly that’s a question that needs to be answered, and any policy needs to take this into account, unless we go as big as the solar panel subsidies did. Yet what we know we have is a suppressed economy, looking to emerge from a demand-side slump, and this a lever there to be pulled

Setting aside budget to pay people getting rid of their smokey old daily driver for something new (not our beloved garaged classics) is an argument worth pursuing. It would put liquid capital into the economy chain, while helping clean up the air and making drivers safer at the same time.

I’m no economist, but by learning lessons from our own past and from other nations, we can craft a program that kicks goals.

Please, tell us your thoughts in the comments.

Max Davies

1 Minute Ago

Damion Smy

8 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

9 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

11 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

13 Hours Ago

CarExpert.com.au

14 Hours Ago