In motoring circles, kerbing (the act of grinding the outer rim or spokes of a wheel on a kerb, roundabout or other immovable object) is akin to a heinous crime punishable by a press-car ban, company-wide ridicule or in the case of repeat offenders – possibly your marching orders.

It’s an act that’s deemed to be totally avoidable and one that requires an immediate phone call from the perpetrator to the PR head of the automotive brand in question. Not a call you want to make.

While I don’t recall ever being read the riot act or anything like that in the earliest years when we kicked off the now-defunct CarAdvice, it was simply an unwritten rule of law that you don’t kerb wheels for fear of not getting another press car from said manufacturer.

It might seem like a minor breach in the scheme of things, compared to panel damage, or worse still, total and utter annihilation of a car on track. But not in our world, where ‘kerbing’ is widely recognised as the ultimate rookie error, it’s deserving of relentless ridicule.

But let’s face it, we’re all human and we all make mistakes, usually under pressure, like parallel parking on a busy street in the CBD, with a line of impatient traffic bearing down on you, already incensed by the micro delay in forward progress as you attempt to back your car into an especially tight spot. We’ve all been there.

It’s times like these when disaster usually strikes, and generally only when you’re behind the wheel of prestige model chock-a-block with expensive options including forged alloy wheels with outward-protruding diamond-cut spokes.

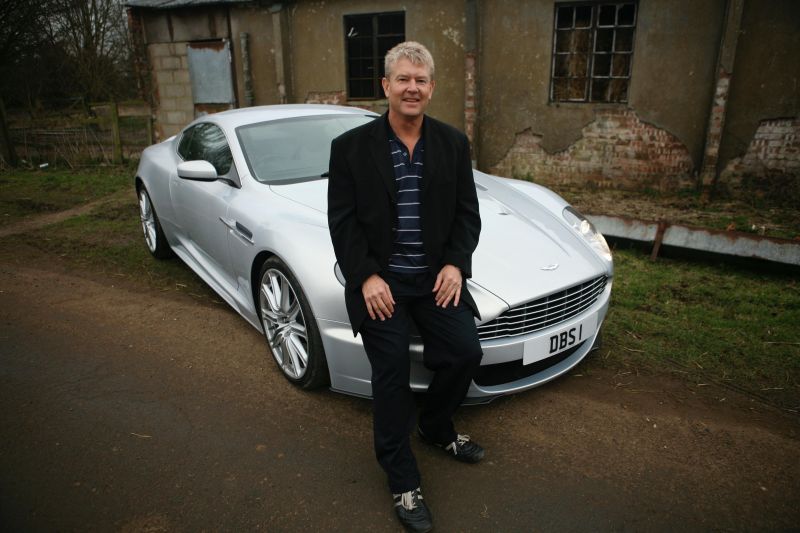

You tend to go into shock for a few minutes, but not before hoping (praying), the grinding sound you’ve just felt (and heard) was something else, or that the wheel may have been damaged by the journo who had the car previously – knowing full well it was you who spoiled a perfectly good BMW M3 or in my case, a spanking new Aston Martin DBS.

I think it was 2008, not long before Alborz, Paul and I left to drive the Bugatti Veyron in France, among other exotics in Italy and the UK. It’s not that I was living on a busy street or anything like that.

In fact, it was a steep cul-de-sac, but not a very wide one, so my intention was to park the Aston as close to the kerb as possible to mitigate the risk of mirror damage, or worse. That’s the first mistake. Leave plenty of room for error is the rule of thumb these days.

The moment I heard that unmistakable sound of metal being ground away by concrete, I genuinely felt ill. Sick with regret and a feeling like the whole thing was surreal and couldn’t have happened to me.

I was hoping for the best, praying the damage was insignificant and barely noticeable. More self-delusion right there, until I got out and saw the damage, accentuated by thousands of metal filings and a ruined 20-inch Italian-made OZ wheel.

Worse still, we had just been appointed the exclusive Australian representative at Aston’s global launches, so I immediately decided I wasn’t going to make that call. Not today. A subsequent tip from a friend who owned a tyre business put me onto ‘Merlin the magician’ – who could fix exotic wheels like new for a few hundred bucks, but he needed the car overnight.

Sh.. it was supposed to be returned that same afternoon.

In the end, I managed to delay the return, and you simply couldn’t tell there had ever been any damage. Remarkable skills, but I still feel guilty to this day for not having come clean. ‘No one ended up worse off’, was how I justified my actions.

These days, with the advantage of left-side door mirrors that automatically dip to afford a better view of the kerb itself, there’s simply no excuse.

If only my wife shared the same attitude. Every wheel on the family Volvo XC40 has been unconscionably decimated. Worse still, she seems to have no recollection of the hideous grinding sounds that would have accompanied such multiple acts of ruin, and yet her hearing seems to be very acute.

After a ‘rimming’ event like that with the DBS, you naturally tend to take more care when it comes to kerbside parking, or indeed, wheels in general. A valuable lesson learned, as it turned out.

Arriving at Bugatti’s Automobiles S.A.S. at 1 Chateau Saint Jean Chemin de Dorlisheim Molsheim, in France, put an entirely different spin on the potential for wheel damage.

Already nervous about getting into a $4 million car, I was put through several tests designed to expose any lack of driving ability or tendency to suffer from motion sickness. One of those tests was to take the Veyron up to 300km/h in a furious burst before hard braking into a roundabout, which itself had to be taken with the throttle flat – ‘to experience the insane levels of grip from the enormously wide 365/710 ZR 540A bespoke rear tyres’, apparently.

I must have passed, because we had the car for two days and speeds up to 365km/h were reached (if Alborz is to be believed). But, the principle instruction from Julius Kruta, head of the Bugatti brand, was to not damage the inordinately expensive rims, which retailed at a staggering €40,000 a set, or $62,000 in 2009.

Moreover, Julius didn’t leave us alone for a minute over those two days, and most of the roads were twisty and rather narrow. You can imagine the fear. Damaging the rims on a Bugatti simply wasn’t an option, despite having to emulate the performance driving from a guy who had more than a 1000 hours behind the wheel. Oh, and we were shooting a video as well.

While somehow avoiding any ruin with the Veyron, genuine disaster struck soon after in Germany, not far from the Nürburgring while driving a one-off BMW M3 by Brabham Racing. It was a monster-powered version of an M3 that looked like it had overdosed on steroids and wore a set of bespoke carbon-fibre wheels – the design of which included multiple finely-fashioned carbon spokes that bent outwards.

I remember the scene like yesterday. Alborz was behind the wheel and instead of looking at the narrow roads ahead, he turned away to look at the camera and pow, or was it ‘boing’?

The engineer/minder for the BMW, Alex Zilliger, was on the phone speaking to the owner of the company at the precise moment when the wheel collided with the gutter and the single carbon spoke ricocheted somewhere off into the Black Forest.

It was as if the blood had completely withdrawn from his face. I think Alborz had gone into shock at precisely that moment, because there was a delayed reaction before he muttered, “What was that noise?”, knowing full well what his catastrophic actions had meant. You can only imagine my response, as this drive was to be the first of two, one-off cars.

From that moment on he believed the car to be cursed, so I swapped into the driver’s seat with only minutes to decide our immediate course of action. In the end we got to drive the outrageous Veritas RS111 around Lake Garda in Italy, but only after copping the blame for daring to allow an unauthorised person to take the wheel.

We’re still friends with Alex, who fabricates exquisite carbon-fibre parts for BMW M cars. Go figure.